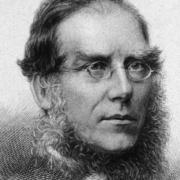

Whether she’s chained to a radiator in the recent TV thriller Wolf, buried in sand on stage for Beckett’s Happy Days, or suspended on a trapeze as a stroke-sufferer for the play Wings, actor Juliet Stevenson always astonishes audiences with her extraordinary and memorable performances. Her ‘ugly crying’ in Anthony Minghella’s 1991 film Truly, Madly, Deeply has been credited as the source of a whole new tradition of high emotion portrayals.

‘I like to try something different, something extreme,’ Juliet says of choosing parts throughout a television, film, radio and stage career that's now in its fifth decade. ‘If the role is going to involve something I haven’t done before, it will be much more appealing. I don’t want to repeat myself if I can help it, so I’m trying to jump ship a lot. And I’m passionate about new writing.’

Juliet has had a home in the county for almost 20 years; she was introduced to the coast and countryside near Southwold when filming Drowning by Numbers there in 1987.

‘We were shooting in the area for about eight weeks and it was a revelation to me,’ she says. ‘I’ve always loved hills and rushing rivers, so I’d never given East Anglia a lot of thought, but I fell in love with the landscape – the huge skies, the light and the water, and the fact that every day it looks completely different.’

Years later, Juliet and her husband, anthropologist Hugh Brody, were looking to buy a property. ‘We’d been longing to get out of London, but it was pointless. I’m often in the West End so how was I going to get back after a show? And I didn’t want to spend my whole time trying to get home to see the kids.’

Suffolk, they found, was within travelling distance of their commitments in London and satisfied their desire to live deep in the countryside. After some searching they discovered a cottage in the same lane as their good friends, near to where Juliet had first filmed in the county.

There have subsequently been lots of trips to and from Liverpool Street. ‘I love trains and I really enjoy the journey from Darsham to Ipswich. I love looking out of the window and seeing the masts of the boats beside the track at Woodbridge. The train station seems almost to be in the harbour.’

Speaking to me in a brief respite between stays in Iceland, where she's filming a new TV series called King and Conqueror, Juliet acknowledges that life, family and commitments have always been a juggling act.

‘I’ve been so lucky. I haven’t really had much time not working. In fact the lockdown was the first occasion I’d ever actually stopped for any period and could do other things.’ First recognising her love of performance when reciting poetry at school, Juliet went on to study at RADA. Just three months after graduating, she was called up by the Royal Shakespeare Company to replace an actress who had broken her foot.

‘It was the bottom-of-the-pile contract,’ she says. Her first appearance was as a barking dog in The Tempest. But bigger, more significant roles quickly followed. ‘I was sort of spotted in the old-fashioned way and people gave me opportunities, with lots of help.’

‘There was the famously brilliant voice coach, Cicely Berry, who was giving classes every morning and John Barton’s sonnet classes, and David Suchet giving acting workshops at the weekend. And in the wings, I was watching great actors. I was given so many opportunities to go on learning.’

She’s eager, then, for the INK Festival to offer the same safe space in Suffolk for writers to learn from each other ‘in a helpful creative apprenticeship’.

‘This country is so rich in talent, producing great writing, great acting, great design, visual arts, music. We are looked to by the world, yet our councils and government don’t understand the connection between investing relatively small amounts in the arts, and the payback.

‘Nobody goes straight from their back bedroom to writing for Netflix. They have to practise somewhere and places like INK are where they start. The writers at the festival today may well be writing a prime TV series in five years’ time; that’s the way it works.’