Svend Bayer has been making pots for over 40 years...

but has he made the perfect one yet?

Words and pictures by Caroline Rees

Clay, Wood and Shells

Svend Bayer has been making pots for over 40 years...but has he made the perfect one yet?

Words and photos by Caroline Rees

When black smoke rises above the hedgerows on the outskirts of Sheepwash, it’s probably a sign that potter Svend Bayer is “gambling” on his latest firing. As his kiln strains under extreme heat, he has no idea, even after 40-plus years, if the pots will be to his liking – or whether he will have to dump the lot. “I have a loss rate that makes me cry,” he smiles, “but when things go right, the results can be stunning.”

The characteristic dribbles and flecks of colour on his pots can only be created by long wood firings, which require round-the-clock stoking at temperatures exceeding 1300°C. When the wood ash lands on the pots, it melts and drips, and reacts with the silica in the clay. His signature scallop-shell imprint is created when the shells, which he uses as pot separators in the kiln, become fused to the clay.

Modestly, Bayer points out that Chinese and Japanese potters have been doing all this for several thousand years. “I haven’t invented anything.” He produces a range for the David Mellor kitchen shop in London’s Sloane Square but his stoneware pots are formed from the North Devon landscape around him – made with local clay and fired using local timber. They are highly desirable and collectable.

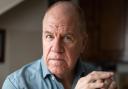

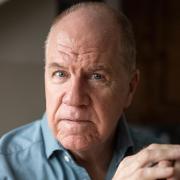

Bayer was born in Uganda to Danish parents 66 years ago. He is softly spoken, with twinkly blue eyes, wild artist’s hair, spattered jeans and a world-weary wit. He has had his studio at Sheepwash since 1975, but until a romantic encounter at Exeter University, his only experience of ceramics was making clay animals as a child.

Having been farmed out to six different schools in four different countries, Bayer ended up studying geography at Exeter. “It didn’t interest me at all. But I did meet a girl whose previous boyfriend was a potter. We began to visit potteries and I loved it.” When she gave him Bernard Leach’s A Potter’s Book, the work in it which attracted Bayer was by another ceramicist, Michael Cardew. “I wrote to him, went for an interview and he took me on. When I found pottery, that was it for me.”

At Cardew’s studio on Bodmin Moor, Bayer learnt to make the giant pots, measuring 2ft across, which have made his name. The challenge appealed to him. Bayer starts by throwing a large bowl, then adds clay in coils to form the top half. “The big pots that excite me have a real presence, a serenity. I’ll work on them for about four days. When I’m being really pompous and people say ‘It didn’t take that long. Why are you charging so much?’, I say, ‘Well, plus the other 43 years!’.”

The price tag for a large garden vessel when he exhibited at Bideford’s Burton Art Gallery last summer was £10,000. Even he seems surprised that this doesn’t deter buyers. “People just want one and they’ll save for it. One customer in Kuwait bought them by the hundred. Unfortunately, the last consignment went out just before the Iraqi invasion so I’m not sure if any survived.” Not all his work is that expensive, though. Medium-sized jugs are around £100.

Bayer is much more interested in making pots than wondering where they end up. It is in the kiln where his artistry comes to the fore, however much of a gamble it may be. His garden vessels are patterned solely by melted wood ash that has run across the surface. His glazed wares – he likes shino and celadon glazes – offer more colourful markings. “I’m a sucker for a gaudy pot,” he says.

The effects are determined partly by the amount of oxygen inside the kiln. “The best colours tend to be in a reduction atmosphere, where there’s not enough air so nature leeches oxides out of the clay and the glazes.” Firings last 3-6 days and he has help from two women friends. “You have to watch the flame all the time. We each do four-hour shifts. To begin with, you’re stoking every 20 minutes, then every five.”

“He used to send a tractor over to collect the clay until the company stopped doing business that way. He blames men in suits with no imagination!”

Despite often spectacular results, he claims to have little control over the outcome. “The most I can do is hope for something that has happened before. If your stoking goes awry and there’s oxidisation, the colours can be very dull,” he says. Other problems occur: “Often you find nice pots stuck together or broken. I’ve had big pots explode, which sounds like rifle shots.”

Over the summer, Bayer was exasperated that each of his firings had been progressively worse. The kiln is packed with hundreds of pots so there’s a lot at stake. “Often, the first few pots will be great and I have this slightly manic phase, then it gets worse and I go into a deep gloom. I’ve thrown away work because I didn’t want to be associated with it. I smash it into tiny shards. I don’t feel angry. I feel stupid. But when it’s good,” he adds brightly, “that feeling is in a league of its own.”

It’s the risk that keeps it interesting. “I wish it wasn’t such a gamble. But I take my hat off to people who fire with oil, gas and electricity and haven’t got bored because so far as I can see what they’re getting is totally predictable.”

Bayer is a very self-sufficient potter. He builds his own kilns, makes his own glazes and has even grown some of his own timber. He settled in Sheepwash because of the proximity of the ball-clay mines at Peters Marland and Meeth. He used to send a tractor over to collect the clay until the company stopped doing business that way. He blames men in suits with no imagination. “The clay is why I’m here, so it’s a shame.” He still uses it but it’s made up for him now in Cornwall.

After 37 years as “the archetypal outsider”, he is just getting known in the village, he smiles. He accepts that he was probably viewed as the mad artist with the foreign name beavering away in the little thatched cottage. “This year, they invited me, an unreconstructed hippy, to open the village fete. I was really honoured.”

He has just completed his 18th kiln, a mini-cathedral of domed brick construction. Building them is as satisfying as the work he puts in them, he says, but the effort is taking its toll and now he no longer has a family to support, he’s sensing a new phase in his work.

He has been inspired to experiment by the work of another potter who uses glazes from crushed quarry stones and gets colourful results from short firings. “Dartmoor and Bodmin have quarries, so it seems like a real possibility. Boy, if I could stop doing long firings, I would love it. I’ve made thousands of big pots. There’s nothing to prove any more. As for firing them – they occupy so much room, then they break, then people don’t buy them…” He laughs at his outburst and checks himself. “I don’t want to sound negative. I’ve been incredibly lucky. I’ve made almost no compromises in my work and got away with it.”

What keeps him doing it? “I have to make a living, but I think I’m obsessed. I don’t want to get all heavy but somewhere in my mind, I have a perfect pot… and I haven’t quite made it yet.”

Svend Bayer: 01409 231282. A selection of his work is for sale at the Burton Art Gallery, Bideford. See also goldmarkart.com/scholarship/svend-bayer-potter/