It's easy to forget - even when the evidence is still all around us - that the Cotswolds played a crucial part in Britain's war effort

For Peace on Earth

‘Peace on earth!’ was said. We sing it,And pay a million priests to bring it.Thomas Hardy ‘Christmas’

The Christmas cards are still festooning our walls and window sills, cupboard tops and mantelpieces, proclaiming the age old sentiments of wishing for peace on earth and goodwill to all men, although the last notes of the carols have faded into Christmas just past. Thomas Hardy, our West Country poet, was reflecting on the ‘war to end all wars’ when he penned his words just a decade after the Great War had ended – seven decades on since the outbreak of the Second World War those words still form a fervent prayer for peace in the world as another new era dawns and many thoughts turn back to that time when the country was called upon to fight for that peace. Hardy also declared that ‘War makes rattling good history; but Peace is poor reading’.There has been a remarkable interest in the history of wartime as remembered by the generation that lived through it and both the official documents on the restrictions and regulations, and daily life lived in accordance with, and in spite of them make incredible if not ‘rattling good’ insight into that period in our history. So, how was our peaceful corner of Britain affected, and what part did our peace-loving folk play in what became a world at war? My grandfather muttered darkly about what he took as a personal affront and insult to the better judgement of the small Coln Valley village of Quenington that war was declared, despite his efforts at getting some 300-odd souls of the parish to sign a Peace Ballot. During my research to try and build up a picture of the Cotswolds at war, I was delighted to find that Grampy Lewis’s efforts to keep peace on earth – though in vain, as it turned out, were locked in to the statement of the Quenington Parish Council Minutes of 25 July 1935: It was proposed by the Chairman, Mr A Hobbs, and seconded by Mr Pink, that a resolution be sent to the League of Nations or National Peace Council stating that we do not want war. No wonder he nursed his indignation to the end of his days as war broke out some four years later.Life in village and town, city and countryside was turned upside down as the folks at home set about defending their home patch against the real threat of invasion; the influx of children from vulnerable cities and coastal towns doubled the size of the village schools and family homes bulged with evacuees. Playing fields went under the spade as every bit of land was turned over to grow food; factories changed production, mothers turned their hand to munition work and hairdressers joined the Land Army; grandmothers sacrificed saucepans to help make Spitfires, and every schoolchild became a skilled fruit-and-nut hunter of the hedgerows – all for the War Effort. Austerity as well as necessity became the mother of all inventions: conkers turned into munitions, corsets to parachutes and camouflage created a culture all of its own as kerbs were whitened and windows blackened.The first Christmas of the war brought forth boastful reports in the local papers (known to be a source of information followed closely by German Intelligence) of how joyful the feasting and merry-making were in England compared with what German people were having to make do with. ‘Cheltenham enjoyed an excellent Christmas, thank you, Mr Hitler. The turkeys were plump and toothsome and the mince pies and plum puddings sizzled. The traders had a splendid Christmas. We defied the black-out and danced till two in the morning with paper hats on our heads. How your people would have loved it.’ Although not quite so effusive in description and provocative in style, the following year’s reports still aimed at trying to put across a reassuring feeling that things were not too bad after all. The Citizen of 5 September 1939 warned ‘Nazis are Watching Parish Magazines’ and the Minister of Information appealed to the editors of 40,000 technical and religious magazines, through the Censorship Division, to follow the lead of the national press and make no reference to incidents that gave identification of place and persons. Such was the suppression of detail and reconciling the responsibilities of a free press with stringent censorship that editors and journalists were constantly frustrated as to just what to report and publish. It was summed up in a cabled report to the Chicago Daily News: An undetermined number of bombers came over an unidentified portion of an unmentioned European country on an unstated day. ‘Recently’ is the official word for it. There was no weather. Had there been, it would have been considered a military secret. The alert sounded at no particular hour because the enemy – one hesitates to label them with a proper name – are not supposed to know the right time. The report was passed by the British censors!Posters warned against scare-mongering and careless talk, but rumours were rife – just as the Cotswold author, Reginald Arkell, had written of in the course of the First World War. Actual evidence I have none, But my aunt’s charwoman’s sister’s son Heard a policeman, on his beat, Say to a housemaid in Downing Street, That he had a brother, who had a friend, Who knew when the war would end. Reginald Arkell was so amused that so many people quoted the lines and carried cuttings of them in their pocket that ‘they imagined themselves to be the author of them!’ He duly acknowledged the public adoption of his verses in his subsequent book War Rumours, published in 1939. ‘My grateful thanks are due to those many excellent authors who have allowed me to print the verse that appears in this little book. The fact that I wrote it myself does not lessen this sense of obligation.’There had been a definite optimism during the strangely quiet spell following the declaration of war that it would be ‘all over by Christmas’. That was not to be, but no one could foretell that it would be six long war-torn years before it was to end and even longer for a true peace and security to be achieved.The Cotswolds were designated as a ‘safe area’, hence the high number of evacuees, but the rural idyll was to be shattered as the war intensified and key aircraft industries settled in the foothill vale, attracting devastating air raids. Airfields and landing strips mushroomed over the rolling wolds and tucked into the folds of the valleys to become strategic pivotal points for the invasion of Europe, and American troops introduced a whole new culture to local villages. Units of the legendary SAS and SOE trained in tented compounds and within castle walls, Radar was developed in a country house at Malmesbury and an important cell of the British Resistance, which was known as Churchill’s Secret Army, were, literally, an underground movement at Coleshill Estate, with a Miss Marples figure of a postmistress as a crucial link. And we must not forget brave little Kenley Lass – awarded the Pigeon’s ‘VC’ for meritorious performance on war service – the Cotswolds thus claiming to be the first to use the National Pigeon Service successfully.

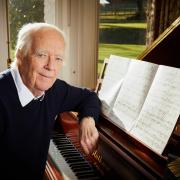

The Cotswolds At War by June Lewis-Jones is published by Amberley Publishing.