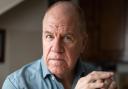

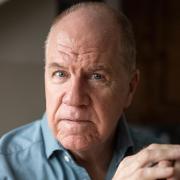

Simon Hulstone, of Michelin-starred The Elephant restaurant talks to Catherine Courtenay about his career as a competition chef

He never went to restaurants, he didn’t even own a cookery book, but by the end of his teenage years Simon Hulstone was a world champion chef.

Simon, who began his career as a kitchen porter in Torquay’s Imperial Hotel where his father was executive chef, spent his formative years dedicated to the world of competitions. The teenager would travel to London to compete against hotels like the Savoy and the Ritz. Winning titles as a young chef led to job offers and bigger opportunities, including the chance to travel the world as part of culinary teams competing in some of the world’s most prestigious events, like the Bocuse d’Or.

“Competitions stopped me from being bored,” says the man who’d sacrificed the excitement of playing football at the weekends to work in a kitchen. “I got to do something different, but stay in my industry.”

Both Simon’s father Roger, and the chef he was apprenticed to, Freddie Jones, were seasoned competitors. It was the world Simon grew up in.

“For me it was fantastic. Other chefs looked at it as a lot of old boys telling chefs what to do, but it was exciting and fun to go to London. Get up early, do your competition, see all the chefs, it was interesting.”

At 16 he’d become a European champion and the world title four years later led to a rush of job offers. But he rejected them all and moved to New Zealand where he became New Zealand Young Chef of the Year.

There followed a period when he describes himself as a “competition mercenary”. “I got paid to travel and compete – South Africa, Australia, Malta, Canada, Korea – I was bouncing from competition to competition and being paid to do it and stay at fantastic hotels.”

It’s hard to comprehend when Simon says, it was seven years before he set foot in a restaurant and that he was oblivious to fine dining awards like Michelin, but he explains that competitions were very much what hotel chefs did; restaurant chefs were different.

“Competition chefs were looked down on by restaurant chefs because apparently we could only cook one dish and that was it. But we looked at restaurant chefs as just cooking spinach and peeling garlic, because that’s what they did most of the time, and thought they were too scared to compete! A chef from Marco Pierre White didn’t want to lose against a guy from Travelodge.”

“I was in a bubble of big hotels where the only way you’d get noticed was to win competitions,” he continues. “I didn’t know anything about restaurant awards, but that gave me an additional perspective, something else to win.”

The competition path taught him valuable lessons about organisation, consistency and the use of flavour and ingredients, skills which he utilised when he started to promote himself as a restaurant chef.

“I started to get noticed by the Guides, then I started winning the awards in the restaurant and different people started noticing me, not just competition chefs. It was: ‘He does comps and he can cook!’ ”

The world of the competition chef may seem a dazzling and starry world, fraught with drama and tension, but most times it’s just a case of reading the rules and doing what they ask. Simon recounts a tale about when he won £8,000 in a competition run by Lea & Perrins.

“There was a guy making jellies out of the sauce, but all I did was mix it with little ketchup, some pineapple juice and spring onion and put a little dipping sauce out with steak and chips. And that was what they wanted; because they could put it in a jar, and call it Lea & Perrins spiced ketchup. Sometimes something very simple will win! Jellies? It was a lovely dish, but they’re not going to replicate it are they? Silly boy!”

Cash prizes aside, the most rewarding highlight for Simon has undoubtedly been winning the Roux Scholarship in 2003. It made him part of a small but elite group of UK chefs, and he was also invited to become a judge for the competition. Being a scholar means he gets to go on educational world tours, organised by Michel Roux Snr. “They are the most unbelievable food trips you could imagine,” he says. “The access that Michel Snr and Michel Jnr have in our industry is unparalleled, so we’ve seen everything that everyone dreams of. It’s life changing.”

He’s earned a reputation for mentoring and helping other young chefs follow the competition route, although he says it’s not as popular now as it once was. “If they have a sparkle I’ll help, but some want to do it for the wrong reasons.

“So many of them want to be a head chef before they can cook. I blame TV a lot as they all think they’re going to become superstars,” he laments.

He points out that it took many attempts, and several years, before he ever won a prize, but he learned from his mistakes and kept trying.

“Just winning a competition doesn’t make you the best chef in the country,” he warns.

And any final words of advice? “Don’t wear silly trousers and a bandana; have some respect, work in a kitchen and learn your craft. If you’re going to be famous, you’re going to be famous.”