At the height of the wool trade, it is estimated that half a million sheep dotted the Cotswold Hills, says Hermione Taylor in the fourth part of her fascinating series on things that made the Cotswold economy

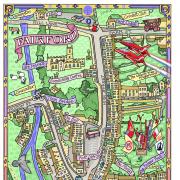

Burford – the southern gateway to the Cotswolds, and (according to Forbes Magazine) one of the most idyllic places to live in Europe. I like to start a visit down by the River Windrush, stopping to peer up at the towering spire of The Church of St John the Baptist. Then I head up the hill and turn down Sheep Street, with its almost village-green-like grass verges separating the houses from the road ahead.

The Lamb Inn sits to the right: opened in 1400 to provide lodging for wool merchants, and still a great place for a drink today. And when I eventually stumble back out onto the High Street, I might stop to admire the old merchant meeting place on the ground floor of the Tolsey building. Even after a stiff drink, you can’t help but notice that Burford’s landmarks, landlords and layout seem to be shaped by sheep…

In medieval England, wool was big business, and it was even said that ‘half the wealth of England rides on the sheep’s back’. By the 1300s, wool was seen as so important to the English economy that the Lord Chancellor’s seat in the House of Lords became a woollen bale, known as ‘the woolsack’ in a tradition that still endures today. By the Stuart period, legislation was introduced to keep domestic wool consumption high and this vital industry afloat. This included the rather macabre Burial in Wool Acts, which stated that all bodies had to be buried wearing woollen clothes – apparently the origin of the phrase ‘to pull the wool over someone’s eyes’.

And wool wasn’t only popular with English customers; it was a prized export too. As early as the 1100s, Cotswold merchants were exporting wool to Flanders, and there are even records of a song sung by medieval weavers that extolled: ‘The best wool in Europe is English; and the best wool in England is Cotswold!’

The rolling hills and open pastures of the Cotswolds were ideal terrain for grazing; at the height of the trade, it is estimated that 500,000 sheep dotted the local hills – a huge number, given the population of the entire country was less than two million at the time. The Cotswold sheep is one of the oldest English long wool breeds, and is thought to be descended from the ancient flocks bought to the area by Romans.

The modern Cotswold sheep is easily recognisable, with its heavy wool and long ‘forelock’: this thick, curly fringe also gives the breed its nickname of the Lion of the Cotswolds. Cotswolds also have a naturally creamy-coloured fleece, which became popular as a sign of quality with customers. There are even stories of medieval traders ‘enhancing’ this by adding yellow ochre to wool to create a truly golden fleece.

And Cotswold wool proved ‘golden’ in more ways than one, with local merchants growing extremely rich from the proceeds. These traders spent lavishly on their houses; in Chipping Campden you can still see the palatial Grevel House on the High Street, built in the late 1300s by a trader known as the ‘flower of the wool merchants of all England’.

These merchants also made generous contributions to local churches, hoping that their generosity would ensure a place in heaven. So-called Cotswold wool churches are often enormous compared to the towns and villages they sit in, and look more like cathedrals than parish churches. They are also some of the most adorned and elaborate in the country, and among their decorations are some terrific references to the wool trade. Burford church has an ornate wool-roll topped tomb; the porch of St Mary’s Church in Chipping Norton features a carving of a sheep overpowering a wolf, and the church of St Peter and St Paul in Northleach has a whole collection of medieval brasses commemorating local wool merchants and their trade.

Now home to fewer than 2,000 people, it seems incredible that Northleach boasts such an imposing church. But its grandeur is thanks to the generosity of some very wealthy medieval donors. One brass from the mid 1400s shows an image of John Fortey, a wealthy wool merchant who bequeathed £300 for the complete restoration of the church. He is richly dressed in a fur-lined cloak, and evidence of his profession is everywhere – he even wears a belt inscribed with his wool-mark, and one-foot stands on a sheep; the other on a woolpack. Another brass from 1525, shows Thomas Bushe and his wife Joan. Their figures are shown under a canopy of three sheep under a bush – a pun on the family name and a reference to the wool trade to boot!

Women are actually rather well represented in the brasses – Mawd Parker Thomas has a brass in her own right, and several women feature with their husbands. One shows a woman called Agnes, standing at the centre of the effigy, flanked on either side by her two husbands. And another brass from the church even suggests that women may have played an active role in the trade itself. Near the pulpit is a brass of another wool merchant, William Midwinter who grew rich from trade with Calais merchants. He is shown next to his wife, Agnes, who also stands with her feet on sheep and a woolpack – suggesting she may too have been a merchant in her own right.

But it wasn’t only grand merchant houses and imposing wool churches that were shaped by sheep – entire towns evolved to accommodate the wool trade. In Burford, the grass verges lining Sheep Street were designed to hold sheep as they made their way to market. In Stow-on-the-Wold, up to 20,000 sheep would congregate on market day, and a network of alleys called ‘tures’ would funnel to them to Market Place. Legend has it that these were designed to allow merchants to count the sheep as they left the market, and you can still try to squeeze down one that runs between the Talbot and the Pharmacy today!

Some even say that the word ‘Cotswolds’ itself stems from the wool trade: the ‘cots’ referring to sheep enclosures, and the ‘wolds’, the rolling hills where they graze. Today, Burford, Stow, and Chipping Campden still have a Sheep Street, and the names of entire villages remind us of how important sheep once were. Sheepscombe, Shipton-under-Wychwood, Shipston-on-Stour and Shippy Grove commemorate the sheep themselves, whereas Sherborne refers to ‘the brook where sheep are sheared’.

But, though still home to almost a quarter of a million sheep, you will be hard pressed to find a Cotswold Lion on a walk through the fields today. The breed nearly died out after the First World War, and it is only thanks to a concerted conservation effort that over a thousand sheep still survive. But, if you would like to see a famous golden fleece for yourself, you still have the chance: you can visit the Cotswold sheep at Cotswold Farm Park, see the best in show at Moreton Show, and even sample Cotswold lamb from Conygree Farm.

References

- Northleach bronzes at the church of St Peter and St Paul: bit.ly/3KcCp9K

- The Cotswold Wool Industry: britishheritage.com/travel/wool-cotswolds

- The history of Stow-on-the-Wold: bit.ly/3ID8lUB

- The Cotswold Sheep Society: cotswoldsheepsociety.co.uk