Have you heard of Rory Young, asks Katie Jarvis. The extraordinary Cirencester sculptor, and one of the country’s most eminent artist-craftsmen, believes in living life to the fullest

Rory Young is full of generous apologies. He's just back from a swim – hair slightly damp – in Cirencester’s spring-fed lido, a hop, skip and a jump from where he lives. He hasn't had time to eat his breakfast eggs.

‘I can talk and eat,’ he reassures.

‘By the way,’ he adds, pushing towards me a silver sugar-caster. ‘Guess what date that is.’

Goodness. No idea.

‘1750s. It’s got a silver top, which isn’t polished. Mid-Georgian, when sugar was so valuable. Newly coming in from the West Indies. Jamaica.’

‘I’m good on 1485 onwards,’ I say, somehow wanting to impress this man.

‘Beginning of the Tudors. Is that right? And Mary Beaufort? All going back to the Beauforts of Badminton.’

‘Oh dear,’ I laugh. ‘I’m not going to challenge you on any history.’

‘You can! I don’t think my hair is drying out. Open-air pool. Wonderful.’

We’re sitting in a kitchen that enfolds you in its beauty. (A strong word, ‘beauty’. Yet the perfect word.) A huge red Aga; a banner inscribed with Winifred Holtby’s, ‘God give me work till my life shall end and life till my work is done’; books in small stacks on a table that tells of noisy, conversation-filled meals with friends. If you could see into someone’s mind, it would look like this. A crowd of warm memories, images, half-formed thoughts waiting to be collected in a quiet time later.

Have you heard of Rory Young? One of the country’s most eminent artist-craftsmen. The man who worked on restoring the extraordinary stone carvings of the Great West Door of York Minster; who designed, carved and painted seven new stone martyrs for medieval niches in the nave screen at St Albans Cathedral (empty since the butchering Reformation).

‘I really did nearly burn up one of my nine lives on that.’

Because of exhaustion?

‘Working crazy hours to achieve what I wanted. I wanted to take these [St Albans stone statues] to a great level of realism. I was painting them, so that was a complete departure; nobody had done anything like this in my lifetime.’

An unstuffy man, as keen to talk about the memorial he created for a dog – beneath a Victorian doughnut of yew-hedge at Stanway House (for Old Smelly, a beloved Golden Labrador) – as he is about his elevated work in Gloucester Cathedral.

Not heard of him? Well, you probably don’t know the names of the stonemasons who worked on any of our great cathedrals and monuments, either. Men who – certainly with the sandstone of Herefordshire, Worcestershire, Staffordshire – were taken by silicosis at an average age of 35.

‘Sandstone masons died like flies; but you couldn’t kill a limestone mason. Masons in the Cotswolds would live far longer: limestone dust is pretty well harmless.’

But, still, anonymous. Does that matter?

‘It doesn’t matter. Both on the Great West Door of York Minster and on the St Albans seven martyrs, there have been various television features where my name doesn’t appear. And I’m delighted about that. I really am.’

There’s nothing disingenuous about Rory Young. He means what his says. His focus is on honouring a building.

What he appreciates is not praise or accolade so much as the commission itself.

‘Poor old churches. They have to afford insurance; mending a roof that’s been stolen; dealing with dry-rot in the pews. It’s very rare that there’s actually money to put the icing on the cake; to adorn in an artistic way.’

Yet as romantic as some of his commissions might be (‘romantic’ in the sense of honouring individuals in memorials: poet Charles Tomlinson; polymath Davina Wynne-Jones; Rory’s own friend, the extraordinary, indefinable Hilary Peters, who died in February), he’s also a man who deals in the reality of coordinates, measurements; skilled drawings that must prefigure any picking up of chisels. Sculptures aren’t ‘found’ in stone; they’re painstakingly worked and teased out using highly technical skills.

‘This romantic idea that comes from Michelangelo that you’re revealing the figure out of a block of stone… In fact, right back to the Ancient Greeks, sculptors made models and copied from them. A really fine, beautiful piece was so popular that it was reproduced - obviously by hand; but it was done in a mechanical way with the ‘pointing’ method.

‘Eric Gill – a great hero of mine in terms of lettering; and a brilliant designer: Even he, on big pieces, would be working from a model. So everything would be scaled up mechanically.’

Before painting the St Albans martyrs – blue, yellow, pink, green against a halo of ivory stone - Rory referenced the work of cathedral archaeologist Jerry Sampson, who spent a lifetime studying the West Front of Wells Cathedral.

‘Having been trained as a fine art painter [Rory studied at Camberwell], to me colour is an absolute joy in my life.’

Yes… Because we do misunderstand, don’t we, the vivid, vibrant colours with which our ancestors imbued our sacred buildings.

He smiles. ‘Somebody said to me, ‘Only you, Rory, could have trodden the dodgy line between bad taste and high art.’ For me, that was the ultimate compliment.’

His tragedy is that he wasn’t born earlier. Any time up until the First World War – probably up until the Second (bar the Reformation when he’d have lost his enraged head). Any time up until the Brutalism of the 70s, which defined his early years.

‘DID YOU HEAR about the cancer business? I’ve got cancer – did you hear that?’ he asks.

‘Ah, good. Because that’s rather coloured things. This all started in mid-March. Usually, I’d have been carrying on flat out and friends would be kept at bay. Instead, it’s been the most extraordinary year of celebrating myriad friendships and the joy I’ve had in my life.

‘I decided when I heard the fatal news – the dreadful news; the really depressing news from the oncologist – that whereas most people would immediately seek everything available on the NHS, I’ve done nothing at all in that direction. [A pragmatic, far-from-carefree decision.] I just decided to have a party. I literally got in the car; as we were driving back to Cirencester from Cheltenham, I decided I was going to have a huge party called Carpe Diem.

‘Vita brevis; carpe diem.’

As we speak, a clock chimes. A softly alluring sound; a reminder of the ineffable passing of time.

HE SHOWS ME round his house, and it’s amazing. Were it a museum (which it is, without turnstile), each object would have a story-button. ‘Hello, I'm a 19th-century Russian samovar used in a Second-World-War production of Uncle Vanya.’ An 18th-century chimney-pot from Bath: a whitey-smudge of pale cream slip-glaze on the red terracotta. A 150-year-old sickle: ‘Look at the shape of it. Cirencester was well known for edge tools; all down Cricklade Street were little foundries supporting the agricultural industry; before they had horse-drawn binders; before combines.’

A gorgeous, turned, tapering pillar of brick – ‘Guess what this is’ – that once helped form a fire-break in a Bank of England vault. Rory went to Newtown, deep into Powys, to get it from an old lady whose father had been head-gardener for the governor in the 1920s.

In an ‘oratory’ side-room – most surprising of all – I meet full-scale models for the St Albans martyrs, jostling eternally for space.

(Yes, wonderful things.)

A library of limewash that will keep forever: used on Holwell Farm, Wotton (‘Do you know, the night before last I drove by and it’s been painted for the new owners, but still in that gorgeous, original colour’); on Blair Adam in Fife, home of Sir Robert, no less; a Blaisdon-plum-bluey-purple that Rory dug from a claustrophobia-inducing tunnel in Clearwell Caves.

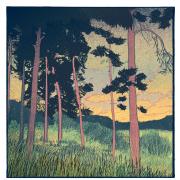

Artwork – including Rory’s own oils, some from a tour of the North of England he embarked on, in the mid-70s, in a campervan. ‘I wanted to see the mills of the north; my England before it was all demolished.’ He lived on £13 a week, parking in laybys, vegetarian by necessity. ‘But I’ve always turned on a sixpence and lived on a shoestring.’

There’s the double courtyard – one after another – full of his work, where the crow of a rooster from somewhere outside belies our mid-town setting.

Later, we get into the car and head down the road to the workshop he’s rented for 30 years, on College Farm where his grandparents – then his parents – were tenant farmers. The farmhouse where Rory was born.

We peer over a wall, between plums and blackberries, to see the red-brick follies he designed and constructed as a 20-year-old, experimenting in the art of buildings.

RORY YOUNG is intending to commission a stained-glass window for Coates church – where he and his sister were baptised – to be created by Thomas Denny, his friend of 42 years. The theme will be traditional agriculture; the agriculture his family practised at College Farm. (A Church that represents, for Rory, the numinous of believers over centuries; perhaps not a personal God – more of a mystery, a language and a heritage of faith.)

Tom Denny has a waiting-list of four years.

‘Whether or not I live to see the window doesn’t matter.’

On the gravestone that Rory Young is designing for himself, there’s a quote from Pericles.

‘What you leave behind is not what is engraved in stone monuments, but what is woven into the lives of others.’

Some people – some very, very few – leave both.

SUBSCRIBE to Cotswold Life magazine for more fascinating Cotswold interviews.