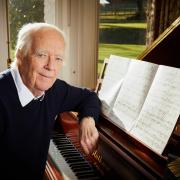

Wildlife filmmaker Gordon Buchanan has had standoffs with wild chimpanzees; been viewed as dinner by hungry polar bears; and saved an abandoned bear cub from starvation. Yet his extraordinary career might easily never have happened, he tells Katie Jarvis, on the eve of his 30th Anniversary tour

The video is spellbinding. Gordon Buchanan plonks himself under a towering tree in a leafy green glade, leaning back against its sturdy, gnarled trunk, canopy way out of sight. A songbird – (maybe a yellow-headed warbler?) (I’ve Googled every which way its bright yellow neckerchief) – sings out joyfully at simply being feathered and free.

Time’s slow march is unhindered by impatience. Gordon is on forest-time: for a tree, a year is a flash; in the sky above, pink-grey clouds move with tortoise-steady crawl.

Then.

As if aware something portentous is occurring, the whole forest freezes.

This is why we are here.

Rustling through woven leaves, textured like cable-knit sweaters, a flitter of movement; a small black shadow amongst paint-catalogue greens. The shadow resolves - short, round ears; huge paws for a slight, furry body; (paws that look as if borrowed from an older, sturdier relative).

A black bear cub, in the wilds of Minnesota. Abandoned. Alone in a careless world fraught with danger.

‘Hey, Hope,’ Gordon whispers to her, as we watch alongside him; silent; alert with concern; soft with compassion.

‘Hey, Hope. How on earth have you managed to make it?’

Gordon Buchanan is looking at me over Zoom. Those kindly, penetrative eyes; that gentle, quizzing voice; that perceptive, knowing mind. I feel as if I should be doing something far more interesting to catch his attention than merely interviewing him. Emerging from hibernation, maybe? Scent-marking? (Note to self: Even if I could, that might not be legal on camera.) [Editor’s note: Apologies to those with vivid imaginations.]

You know the sort of thing: animal behaviour – and I’m just another animal, after all – that Gordon Buchanan has spent more than 30 years gathering on captivating film.

Yet he doesn’t seem to mind that I’m simply sitting, pencil in hand, quizzing him.

‘I’ve been away for the weekend, doing some painting at my dad’s house – painting walls, not pictures - and just got back. So Monday [today] is effectively my Saturday.’

‘Oh – I’m so sorry to take up your ‘Saturday’!’

He shakes his head with a smile. ‘I like to be productive.’

I’m speaking with him because he’s about to take those 30 years on tour: a talk - with video and stills – about some of the highlights of that filmmaking career.

He loves doing talks almost as much as filming. Audience ‘Oohs’ of horror – such as when a simply enormous polar bear (one of the most powerful animals on Earth; an animal that sees humans (literally) as fair game) tries to claw its way through the cage from which he’s filming. ‘A little bit hairy in here,’ Gordon muses, somewhat understatedly, as the cage rocks wildly, the bear’s razor-sharp, blubber-sheering teeth scraping the Perspex between them. (The Polar Bear Family and Me, BBC; Arctic archipelago of Svalbard.)

Or audience gasps – such as when wolves approach (‘…they might approach for two reasons: to see if I’m a threat; or to find out if I’m worth eating’). ‘Hey, Wolf’, Gordon says, between his own gasps, as the animals ominously circle. (No protective cage for this one.) (Snow Wolf Family and Me, BBC Earth, Canadian Arctic.)

And audience chuckles, too - such as at a selfie with an elephant calf. Or a close-encounter with friendlier wolves in Northern Norway, which saunter up and lick Gordon’s face with the familiarity of a cocker spaniel.

But the parts of any show he likes best are Q&As.

‘Often, I’m asked the same questions. [Which he doesn’t mind at all.] But there was one night a man put his hand up and said, ‘Have you ever have five stoats run up your trouser-leg?’

‘I answered, ‘No, but I think I’ve just met a man who has.’’

He needs to add that to his bucket-list, I suggest. Makes his current list of ‘Antarctica’ (‘I’ve spent time in every continent but for that’) seem lacking in ambition.

He’s not convinced.

Thirty years of close encounters of an animal kind.

Actually, slightly more than 30. For Gordon’s story begins in a restaurant on the Isle of Mull: a typical teenager trying to make money by working in a commercial kitchen at evenings and weekends.

…Maybe, even before that. A seven-year-old, living in Clydeside; whose mum decided to move her four children to Mull, even though that meant living cramped in a caravan for the first couple of years.

A move from an ex-ship-building town to the wilds of an island on the west coast of Scotland. ‘And if my mum hadn’t made that decision, who knows what I’d have ended up doing?’

But that’s where it started, running in the wild havens of Mull.

‘Safe?’ he reflects. ‘Given some of the things we used to get up to, it probably wasn’t that safe. But we weren’t out buying drugs – we were walking through woods; going out in boats in weather we shouldn’t have been out in.

‘I just didn’t like being inside – whether that was at home or at school. That desire to feel the wind and rain in my face; not be confined.’

So there he was, barely 17, not a clue what his future would hold. And into the restaurant walked wildlife filmmaker Nick Gordon – then-husband of Ann, the owner - who offered Gordon a job.

Not a washing-up job, either.

Would this teenager – who’d seen so little of life – like to be his assistant on an assignment in Sierra Leone, Nick asked. Mind you, that would mean 18 months away from home, living in a tent in the most primitive of environments, documenting animals in the Gola Rainforest National Park.

Why would he ask you, I quiz Gordon.

I mean, I can (sort of) see the young Gordon’s side. That he’d want to snatch this golden, once-in-a-lifetime, unlooked-for opportunity with both unlined hands. But why would Nick – who presumably had his pick of the crop – choose a naïve 17-year-old, who’d barely been away from home, for such a demanding expedition?

Could have been a nightmare…

‘It could so easily have been a disaster at any point. I have a son who’s 17 and no way on Earth would I pluck him out of our family home and take him off to Sierra Leone for a year-and-a-half.

‘From the minute we touched down, I thought I’d made a huge mistake. I was desperately homesick to the point where I thought that: If I fell out of a tree and broke my leg, I’d have to be sent home. And part of me hoped I would. But I knew I couldn’t turn round to Nick and say, ‘I can’t do this!’’

Homesickness never dissipated. But there were sublime moments that – even if they lasted for less than a minute – dwarfed it. Such as walking through the forest when a huge chimpanzee emerged onto the path in front of him.

‘I hunkered down and we had a bit of a stand-off. As it looked at me, I thought: How many people in the world have encountered a wild chimpanzee face to face? I realised I was an incredibly lucky boy.’

When he got home – 18 months later – his mum didn’t recognise him as he stepped off the ferry.

Bit of an aside. But I think a bit more about that chimpanzee moment. And I realise – watching other of his videos shot in remote, wild, unpredictable places the globe over – that the most scary moments probably don’t involve animals. There’s one where Gordon is threatened by forest fire rapidly cutting off all escape routes. Terrifying.

‘Probably the scariest was when I went to the doctor in Glasgow, feeling terrible and feverish. I said I thought I had malaria. He said, ‘That won’t be malaria’. (In Glasgow, you don’t get that much).’

The problem for the uninitiated is that, if you don’t test blood samples within an hour, you can’t see evidence of this potentially deadly tropical disease.

‘So, every day they were taking blood samples, saying, ‘It’s not malaria. We don’t know what it is.’’

Note to (wonderful) Glasgow doctors: It was malaria.)

SO, I WANT TO ask him about ethics.

And that makes it the perfect time to return to the opening video of Hope, the abandoned wild bear cub in Minnesota. (The Bear Family and Me, BBC.) If you watch a little further (the clip is on YouTube, of course), you’ll see Gordon undoing a flask of milk. ‘It’s got all of your favourite things,’ he tells an unsure Hope. ‘Egg yolk, fish oil…’ It’s enough. In the next frame, Hope is clambering onto his lap, gulping food from a tub he’s holding.

That’s utterly heart-warming.

But is it right?

He’s aware – of course he’s aware – of all the different arguments. But, still.

‘Hope was a bear cub abandoned by her mum. At the time, we thought: Do we just let nature take its course? That bear cub would have died a very slow and unpleasant death [through starvation].

‘Humans are responsible for the deaths of so many bears in North America, whether it’s depriving them of habitat or knocking them down on roads or shooting them. So I thought: This is not a wrong thing to do, to help this bear cub survive.’

And then there was compassion which – as I listen to him talk – seems like the reason in search of a justification.

And bravo to that.

Not that he’s an interventionist per se. Furious posts on social media, during filming for a BBC Springwatch episode, condemned the crew for not saving abandoned seal pups.

‘Monstrous’, they railed.

‘It hadn’t even crossed my mind that we should step in. There was nothing we could do – there was always a chance the mum would come back. But you can’t go round gathering up hundreds of seal pups: they’d spend their life in captivity.’

But… Put your fingers in your ears now if you don’t want the bad news about Hope.

Ironically sad news.

Lily – Hope’s mother – and her cub happily reunited after Gordon’s intervention. After which.

‘Hope was two years old when she was shot, on the brink of leaving her mother; on the brink of independence.

‘I think it was a 12-year-old boy out with his dad - they got a ticket to hunt a bear [in an official lottery]. It’s really tough because, legally, that person had the right to shoot a bear. It’s not something I would want to do but it’s part of life in North America: hunting is a big industry and, culturally, a way of life.’

Gordon is keen to say he’s not against culling full-stop. If deer in Scotland weren’t culled, for instance, ecosystems would suffer.

But Hope?

That was a struggle to come to terms with. ‘That was upsetting.’

WE TALK ABOUT LOADS. About not wanting to anthropomorphise inappropriately. Yet about the pleasure he surely has seen a polar bear expressing. About how a silverback gorilla – or a wolf – with strong bonds to children and family has much in common with a human carer. How a herd of elephants showing joy at the birth of a calf is something we can all understand.

About the responsibility human beings have, as custodians of the planet, to give every species the opportunity for their lives to play out in the way nature intended.

Perhaps spring will help us take stock…

‘When even the busiest of people find themselves standing at a train station or walking through the park, taking notice of things: how the weather changes; how life can return to every neglected window-box.’

And to remember that there’s precious wildness on our Cotswold paths and verges, not just in Sierra Leone.

Gordon is performing 30 Years in the Wild, the Anniversary Tour at The Forum, Bath, March 25; Forum Theatre, Malvern, March 30; Cheltenham Town Hall, April 3; Wyvern Theatre in Swindon, April 11; gordon-buchanan.co.uk