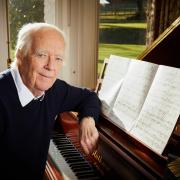

I’ve a 15-minute slot in which to interview Ben Fogle.

I’m not ungrateful. (I’m VERY grateful. Everyone and her dog wants to talk with Ben Fogle (and his dogs).)

And let’s be clear: this is a man who can pack a lot into a remarkably short time. I mean, he only took 18 days, five hours and 10 minutes to cross the Antarctic Plateau (fgs – 480 miles of the least hospitable terrain on Earth).

So, think what he could do with 15 minutes.

Then there was the Atlantic Rowing Race, partnered with Olympian James Cracknell: 49 days, 19 hours and eight minutes to row 3,000 miles, during which their boat completely capsized in mountainous waves. (‘I found myself bobbing up and down in a sea, with waves bigger than houses.’)

Oh, and there was 160 miles running across the Sahara Desert in the six-day ‘toughest footrace on Earth’ Marathon des Sables!

(What I love best about this story is when Ben trucks up in Morocco, ready to set off, only to find himself woefully under-equipped in the essential keeping-sand-out-of-your-footwear department. (My kind of adventurer.)

‘Where are your gaiters?’ asks a baffled French competitor.

Too embarrassed to ask what ‘gaiters’ are (though the Frenchman takes pity and rolls up his trousers), Ben spends his final pre-ordeal hours begging spare fabric from fellow runners so he can stitch ‘Heath Robinson-style’ his own protective legwear.)

And now, here he is: the incredible Ben Fogle, on the other end of a Zoom. (Though no video, for some reason.)

I’ve prepared my questions thoroughly.

‘Gosh,’ I say, admiringly, mindful that I’m one of a conveyor-belt of 15-minute interviewers he’s lined up to talk to. ‘You must be exhausted!’

There’s an infinitesimal pause during which the man – who has (also) climbed Everest, swum from Alcatraz to San Francisco, recreated the epic 430-mile, 1940s desert-trek of Wilfred Thesiger (using authentic-style Thesiger food, equipment, and camel) – thinks about where chatting to journalists comes on the Exhausting Scale.

‘I’ve plenty of energy,’ he lands on, kindly. ‘Don’t worry.’

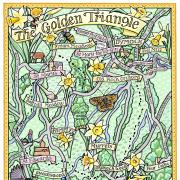

Ben Fogle is about to go on tour again. A live theatre tour. WILD is billed as ‘stories and tales of hope, possibility, and positivity’; his audience will be whisked from adventure to adventure: the wilderness of Northern Sweden, the jungles of Honduras; the hostile extreme environments of Chernobyl, the mountains of Nepal.

A combination of environments and dangers I can desperately yearn to experience in the delightfully safe knowledge that I won’t.

But there’s something specific I want to ask. Because it seems to me that travel – for Ben Fogle – isn’t just about travel.

I’ve no idea what you’ve seen of Ben’s programmes – and there have been many, many different series over the years. But I’ll offer you an early example of what I mean: Extreme Dreams (BBC2, 2007-2009). The series concept was about giving ordinary people an opportunity to do extraordinary things – climbing Mount Baker (Kiyanja) in Uganda; crossing the Sahara in Libya to reach the ancient city of Ghat; trekking through the jungle in Guyana. But the real message was that travel - being taken out of your comfort-zone - could change your life for the better.

Did it work? Few who watched will ever forget Sarah, who joined Ben and co on a trip to Papua New Guinea to clamber the Black Cat Trail (‘suitable only for masochists and Israeli paratroopers’). Sarah, from Wales, had lost her husband – her childhood sweetheart – in a car crash six months previously. So grief-stricken was this young widow, she hadn’t managed even to hold a funeral. Finally, on the summit of Mount Roraima, Sarah says to Ben, ‘Can I ask you a favour? I’d like to hold a service for Simon.’

That’s what I mean.

Ben’s series, over the years, have been full of people such as Sarah (unique people; incredible people), whose lives he has changed or witnessed changing.

So why is travel so powerful?

‘A lot of people look at travel as something very literal – you go to Paris and look at the Eiffel Tower and eat a croque monsieur,’ he begins ruminating.

‘But, for me, it’s so much more; it’s about the smells and the textures and the noises and the people and the language and the encounters – and the good and the bad.’

Yee--ee-esss…

Ish.

I get that his form of travel is not about getting up at 5am to bagsy the best sunbed. But I kind of mean beyond that. Beyond the fact that you should immerse yourself in culture.

It’s more the philosophy: that being somewhere else frees you, almost, from the things that made you; that bind you.

I guess Ben’s New Lives in the Wild is the ultimate exemplar. In the 10 years he’s been making it, Ben has visited more than 100 people who’ve swapped the rat race for lives that are weird, wonderful and, sometimes, so whacky, many rats would avoid them like the plague.

‘The new tour is based largely on those 100 experiences. Every one of them is completely different. I couldn’t emphasise enough how polar opposite many of the people are, or the places, or the experiences that they have had; the things they do. That is what has stopped me in my tracks. And made me re-evaluate my own life,’ he says.

He quotes a couple of his favourites. A Russian father and son who’ve built a ‘Jurassic Park’ in Siberia, trying to bring back the woolly mammoth in a bid to stop permafrost from melting.

A woman whose mother was brought up by monkeys in Colombia, who decided to go and live in the jungle herself.

There are as many stories as people. The high-earning city financier who moved to an island in the Mekong River because he’d never built or made anything tangible. Sandy, who moved to a Greek island and began looking after local stray animals (as in, sharing her home with 25 dogs, 20 cats, eight donkeys, a horse and a mule).

We could go on…

‘So many people are too prescriptive and follow the blueprint of what you’re supposed to do with life; what education teaches you to do; what society encourages you to do. But all these people – all 100 of them (some are families; some are couples) – have broken the chains of expectation and done something a little bit different.’

Indeed, as Tolstoy pointed out: All happy families are alike…

‘These are people who have decided to strip back their life and live a simpler, humbler and – most importantly – happier life. And that’s the heart of it for me – it’s all about being happy. People misinterpret what happiness is. There’s this idea that, when you’re talking about finding happiness, it has to be a guffawing laugh; complete ecstatic euphoria; but it’s not.

‘Happiness is contentment.’

A contentment, Ben Fogle says, that he’s aiming to bring to his live show: feel-good stories to delight each audience.

So, what about Ben himself?

Has he seen a changed life where he thinks: I really envy that?

‘The majority I don’t think I could do myself. There are huge sacrifices that come with dropping off the grid. Often it means you’re leaving – abandoning – family; cutting yourself off from society, friendships, culture; all of those things that many of us enjoy in life. I like the ability to go and buy myself a cappuccino in the same breath that I enjoy being able to make myself a cup of stinging-nettle tea in the woods.’

HIS OWN STORY is an intriguing mix of off- and on-grid.

Ben Fogle loved school, but hated education. An education that mainly took place at Bryanston, a boarding school in Dorset.

‘My first year,’ he writes in his memoir, The Accidental Adventurer, ‘was dominated by debilitating homesickness’. Homesickness so intense, it made him physically sick.

Of course, he eventually settled, made very good friends. Still hated exams. Most of all loved school-holidays at home in Salisbury.

Before starting uni, he took a year out with an organisation called GAP, lied on the form that he could speak Spanish (‘poetic licence, as I liked to call it,’) and got a placement in Ecuador.

Pretty much from then on, the exotic adventures began and have never stopped. ‘I had been in South America for about six months the first time I was arrested…’ is the kind of sentence that follows.

Or try this.

An hour into a flight on a Bolivian Air Force plane into the rainforest (along with passengers such as a woman with three pigs), a sudden jolt pitches the aircraft to one side; when Ben gets off, he sees an ancient fire engine spraying flames licking at the engine.

He witnesses the weird and the wonderful, such as a Catholic/Mayan service in Chamula near San Cristobal, where cola-inspired burping is thought to ward off evil spirits.

Experiences that would make me think twice about catching a bus to Stroud; but, for Ben, they kicked off a life where he’s rarely off a plane.

I STILL THINK Ben Fogle is interesting in a way I haven’t got to the bottom of. (Why would I, in 15 minutes?)

People who know him say what a lovely fellow he is. And that’s certainly how he comes across, in his writing and on screen.

He never bigs himself up. Indeed, he often will make a point of describing how fundamentally unprepared he has been for the most immense experiences. (See above.)

But I do (unlike Ben, I say this with no modesty whatsoever) score one blinder. It comes to me as I read a passage he wrote about seeing for himself Scott’s hut in the Antarctic; musing on the explorer’s brave, tragic, heart-rending final letters, composed as he lay dying after his failed bid to be the first man at the South Pole. ‘Please pass this to my wife’ Scott writes… before crossing out the word ‘wife’ and replacing it with ‘widow’.

Why, Ben wonders, did Scott take these risks; travelling away from things that mattered to him most: his beloved wife and child? And why, Ben wonders by extension, does he do the exact same? After all, Ben Fogle has cheated death – oxygen failure near the summit of Everest; capsizing in the Atlantic; a flesh-eating disease contracted in a Peruvian jungle – more times than I’ve recited Hail Marys on a perfectly safe plane flight.

And then it strikes me. That passage about homesickness, all those years ago in boarding school.

‘I wonder,’ I say to Ben Fogle, ‘whether your travel, even today, isn’t about leaving home at all. It’s the opposite; it’s about recapturing your utter joy at coming home all those board-school years ago. About endurance, followed by euphoria.’

He pauses for a moment.

‘I think you’re spot on with that. I just got back from a month-long trip in Antarctica and I suffered debilitating homesickness when I left; and really did not want to go. But the feeling – the ecstatic feeling of contentment and happiness – euphoric happiness when I got home and spent a long period of time with my children and my wife and dogs and horses was amazing.’

Quite. It’s not so much the travelling; it’s the homecoming.