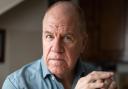

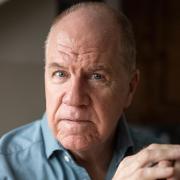

Taking inspiration from nature and the geometry of organic forms, Peter Randall-Page has amassed an impressive catalogue of work over a 50 year career. Mercedes Smith meets him in his Dartmoor studio.

Peter Randall-Page is one of the world’s foremost sculptors. He studied sculpture at Bath Academy of Art in the early Seventies and has since built an international reputation in contemporary art with his inspirational sculptures, drawings and prints. He is best known for his large scale works in granite and marble, which are held in public collections including those of the Tate Gallery, the British Museum, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, The V&A London and venues across the world. Here in the South West his work is on show to the public at the Eden Project, where his monumental Seed sculpture attracts thousands of visitors a year. Wing was acquired by the Royal Albert Memorial Museum (RAMM) and went on display last year in the museum’s courtyard and from July his work will also be on show at Velarde sculpture garden in Kingsbridge.

Peter began his career conserving 13th-century sculpture at Wells Cathedral, and over his fifty years as a working artist he has been a visiting lecturer at the Royal College of Art, an associate Research Fellow at Dartington College of Arts, and a judge of the prestigious Jerwood Sculpture Prize, Threadneedle Prize and John Ruskin Prize. He has been awarded Honorary Doctorates from Plymouth, York St John, Exeter and Bath Spa Universities and in 2015 he was elected as a Royal Academician. Most recently, in collaboration with Grimshaw Architects, Peter was awarded the 2017 RIBA London and RIBA National prizes for his facade designs for Dulwich College.

It is an impressive career by any standard, one that is testament to his single-minded devotion to sculpture, and to the ideas and concepts that he explores through his work, specifically the relationship between man and nature and the mathematics and geometry of organic forms.

‘I’ve been very lucky,’ says Peter, when I interview him at his idyllic cottage and sprawling studio in a secluded Dartmoor valley. ‘I’ve managed to make a living doing what I love. It’s a dangerous thing to do, to pin your most important hopes and ideas to the way that you earn your living, because if it doesn’t work out it could spoil your enjoyment of something that really matters to you.’

What matters in his work, according to his own writing, is his expression through art of natural geometry, ‘the theme on which nature plays her infinite variations’. In person he phrases it differently, saying that what inspires his work is, ‘the extraordinary phenomenon of being alive, in an extraordinary world, and trying to understand how things fit together, and how things impact on our emotions and our feelings’.

What also matters to Peter is the availability of his work to the public. ‘I love doing things which are in the public domain,’ he says. ‘I have done lots of work with the wonderful organisation Common Ground, who gave me a fantastic brief to make works for the public domain over a very long period of time, works without any sort of signage, so that people can just respond directly to a sculpture they find in the landscape.’

Creative freedom, however, is an essential part of public collaborations like these. ‘Creatively I pursue what I’m interested in, and if that happens to come together with a public project through some sort of synchronicity then that’s great,’ says Peter. ‘In terms of what the art world wants, I’ve never really taken a lot of notice of that. You can’t second guess what people are going to be interested in. It doesn’t work. But...’ he adds wryly, ‘I also think it would be hard to go on making things if nobody was remotely interested.’

Considering his immense success as a sculptor, I ask if he has yet achieved his aims in the art world. ‘I don’t think you ever reach what you are aiming for,’ he says. ‘There is always the next thing.’

He has been looking back recently though, in order to put together a new book, and thanks to the creation of his new archive which is housed in a beautiful building on Dartmoor designed by his architect son Tom.

‘It’s an archive and private exhibition space where I can occasionally take my clients,’ explains Peter. ‘Putting the archive together has meant going through an awful lot of stuff, as it has for the book, so I have been in a retrospective mood lately.’

After our interview he and Tom take me down to the archive. It is a modern but understated agricultural style building, but inside it is quite different. Tom’s clever design means that the building opens out to the landscape and closes like a box, and it has an extraordinary sliding cantilevered balcony, which appears and vanishes in one single, smooth motion. Peter wittily refers to this architectural gem as, ‘a cross between a sculpture gallery and Tracey Island’.

It is a wonderfully tranquil space filled with Peter’s sculpture, that includes a climate-controlled storage facility for his notes and works on paper. It is an unusually precious and private space, fit for a man whose career has been built on sharing his talent in the most generous and accessible way.

‘I hope my work is accessible on all sorts of levels,’ Peter says. ‘It is based on lots of ideas that come from my interest in natural phenomena, and mathematics, and music and poetry, but one doesn’t need to know all that in order to enjoy the work. Hopefully people can respond to my work in a very immediate way, and if they want to find out in more depth about the ideas behind it, I hope that that will enrich their understanding of what I’m doing.’

peterrandall-page.com