As a young child Jess Marshall would show her grandfather’s prizewinning cattle at agricultural shows and now she’s 15, fleeces from her flock of Shetland sheep are being turned into beautiful wool which is on sale in a specialist Lancaster shop

Within seconds of us taking a seat in a cosy corner of Northern Yarn – owner Kate Makin huddling next to an indoor heater wearing one of her enviable knitted jumper and both of us surrounded by the glow of vibrantly coloured skeins of wool – the bell to the door of her shop jingles.

‘It’s a bit like a sweet shop in here,’ Kate smiles. ‘Some people ask if I get a bit overwhelmed, which I do sometimes, but then people come in and show me what they have made and I have to make it too. There are not enough hours in the day.’

And right on cue, that’s exactly what happens. A woman here on a day trip from Preston pulls a crumpled magazine page from her handbag and proudly unfolds. ‘I dug out an old pattern I knitted years ago, and I am going to do it again.’

She radiates excitement, and this is exactly what Kate hoped for when she moved here from Camden in 2014.

‘The first thing I did was start up a knit night,’ she says. ‘Really just because I missed my old group and I really wanted to find my tribe. We do something every week – a Monday night and a Tuesday daytime – and it’s just a really lovely, supportive community.’

What makes this place so special is Kate’s connection with local farmers. Ninety per cent of her stock is British and she has processed four of those lines herself – Coorie, Methera, Mamó, and her latest, Selina.

Selina, a woollen spun, heavy four-ply yarn – named after Lancastrian Selina Martin who fought for women’s rights with the Suffragist movement – was made from the fleeces of two Lancastrian women-owned flocks. Diane Gardner, who keeps her Shetland sheep for joy and spins her own yarn from the fibres, and 15-year-old Jess Marshall.

Having grown up showing her grandfather’s prizewinning cattle, Jess’ flock of 15-strong Shetland sheep grew after being gifted three lambs for her 13th birthday.

In the first year, her three fleeces weren’t enough to do anything with, but she was so conscious of the waste that last year – with her chunkier handful of about eight fleeces – she reached out to Kate after finding her on Facebook.

‘It was a coincidence really because I looked around the local area and realised there was a shop close to my school,’ the Lancaster Girls’ Grammar Year 11 student says. ‘I didn’t like the thought of the fleeces just sitting there rotting away.’

Although the list of requirements for processing fleeces can be prohibitive, Kate had a feeling she could make it work – and with another mill space booked for a project that had fallen through, she was convinced it was fate.

‘We invited Kate to come and have a look at the fleeces and she told us it was really good quality stuff,’ Jess says. ‘It actually took us by surprise a little bit because we started out with cattle and didn’t know a whole lot about sheep.’

Jess’ love of farming came from helping her grandad with his Longhorn cattle. He had worked a variety of jobs throughout his life – mainly in prisons – with his last job being livestock manager at HM Prison Kirkham.

It was only when he retired that he bought a couple of lambs to go with his herd, something a then infant-aged Jess was very excited about.

‘Since I was about two or three I halter-trained my grandad’s calves, spending all my time with them,’ she says. ‘I just loved it and begged to go to the farm all the time.

Jess reared her pet lambs and sold them on, making a deal on some Shetland sheep at a sale later that year. ‘I love them to bits,’ smiles Jess, who hopes to be a farm vet when she’s older. ‘I go after school because it’s on my way to my grandad’s; I shout them and they come sprinting down the hill. I just think, this is why I do it.’

Back at the shop, Kate beams as she talks about Jess and her latest yarn. ‘The fleeces were gorgeous – soft and such a fine crimp – and Jess is a natural with animals and has a confidence that belies her years. How amazing that she is only 15 and already thinking she didn’t want to waste this valuable resource?

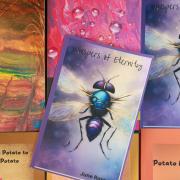

‘This is our first batch and it was small to begin with, but we lost a lot in the processing – making this yarn very limited edition, but hopefully only until next year. It has been skillfully spun in Yorkshire by Halifax Spinning Mill. She’s a beauty and I hope everyone loves her as much as I do.’

‘We used to keep the cows at a big sheep farm through the winter and I was really intrigued by them. I did a couple of days work experience there and really enjoyed it, so I asked my grandad for some pet lambs for my birthday in 2021.’

As part of her mission to change the way sheep farmers are paid for their fleeces, Kate has so far worked with more than 15 local farmers and pays them double what they would get from British Wool. Last year it was reported that British Wool – a Board which collects, grades, markets and sells British wool on behalf of its producers to the international wool textile industry for use in flooring, furnishings and apparel – was paying sheep farmers only 30p per kg for their core grades of 2022 wool (that’s about 75p for an average 2.5kg fleece), with shearing of each ewe priced at about £1.65.

Kate’s passion for the craft comes from her grandmother, who taught her to knit when she was only seven years old. Mamó, meaning grandma in Irish, is worsted spun DK yarn, made from fleeces of Poll Dorset and Bluefaced Leicester sheep that graze on farms around Lancashire and Cumbria, and named after the places she grew up in Ireland.

Her homegrown relationship with local farmers was the starting point to Northern Yarn, having struggled to find British wool locally.

‘Our kids were going to school with sheep farmers and I really wanted to make that connection with where we lived now,’ she says. ‘I got talking at the school gates to a farmer who kept sheep just around the corner; she invited me over and I asked what she did with her wool, because even though I am a knitter, I had never thought about that process.

‘I started to wonder if I could turn it into a job, and then our local wool shop closed. It was as if the stars collided.’

She spent her first 18 months in Lancaster selling small batch wool at market twice a week, from British brands like West Yorkshire Spinners and Lancashire Farm Wool and quickly realised there was huge demand for traceable, British wool.

After that, it was an adventure into the world of processing. ‘I went to my friend’s farm and watched the sheep being sheared, Kate adds. ‘I bought books, studied the fleeces and what makes a good yarn.

‘And then I did lots of ringing around. There aren’t so many mills left in the UK, and they have all got high minimum quantities, costing thousands and pounds.

‘So when people wonder why local, British wool is expensive, it is not the wool itself, but the process.’

Kate’s research led her to Halifax Spinning Mill, based in Bridlington, and she managed to get her first run done with her friend Lynn's fleece. Six months later she had her own batch of wool, and not long after that she signed a lease for the shop, tucked just off the A6 in Lancaster on Middle Street.

‘It was amazing,’ she smiles. ‘And it was brilliant just to go through the whole process of here are some sheep, this is where I live and this wool is actually our landscape.’

Ninety per cent of everything Kate stocks is British. There’s wool from Jamieson’s of Shetland, West Yorkshire Spinners and The Fibre Co; there’s Crookabeck Herdwick wool, John Arbon, Herd and RiverKnits wool; Frangipani Guernsey wool and wool from the New Lanark Spinning Company.

The other 10 per cent comes from brands like De Rerum Natura, a French company which works with local farmers and traditional mills to produce their yarn, and the Icelandic Lopi, a unique, lightweight wool that's incredibly warm and perfect for traditional 'lopapeysa' sweaters with colourful yokes.

‘Before I started Northern Yarn, I would be interested if wool was made from natural fibres because environmentally, that was important to me, and be British ideally, but apart from that I didn’t really think about breeds particularly. If you are not a farmer, how would you know?’ Kate says.

‘I have learnt so much from just being someone who enjoyed knitting; it has been a proper adventure. I am learning all the time about different ways to spin, the different breeds – there are 72 breeds in the UK, and they are all really different.

‘Knitting and crochet tick so many boxes. It is definitely therapeutic – you get into a rhythm, and you can have something easy and mindless, or maybe a bit more of a complicated pattern where you have to focus so you are not thinking about all of the rubbish that comes into your head – and often the first thing knitters and crafters want to do is make things for people, to say look how much I love you.

‘Every day I think I am so lucky to be able to be doing something that I enjoy, and actually it is the people and community that make it so special and make it worth it.’

To find out more, go to northernyarn.co.uk.