Spoiler Alert: This article solves the scandalous mystery!

On Littlehampton’s Western Road, a pretty pebble-dashed cottage sits cosily beside its neighbours. It’s hard to imagine that it was once the site of a battleground – a foul-mouthed feud between two families and a mystery that had Sussex gossip mongers enthralled. So intriguing is this scandal that it is now thrilling cinema goers more than a century later in the film Wicked Little Letters starring Olivia Colman.

The story began in 1918 when Rose Gooding, 27, a domestic, and her husband Bill, 39, a shipyard worker, moved into no.45 Western Road. Whispers soon surrounded these rough-edged newcomers to this uneventful seaside town. Rose, the mother of an illegitimate daughter, was rather slovenly in appearance and would be seen walking around town stockingless and with her hair hanging down. Her non-conformist character and her loose tongue saw her dismissed from her job, further cementing her reputation as a troublemaker.

By contrast, Edith Swan, 30, who lived with her parents in the adjacent no.47, was well-mannered, god-fearing and rather unremarkable. She was engaged to Bert, a soldier posted in Iraq, and spent her days assisting her mother with her work as a laundress.

When Rose’s sister Ruth joined the Gooding household, she brought with her two more children born out of wedlock. Though the living conditions, which included a communal back yard, were doubtless crowded, neighbourly relations were initially good. Edith shared a knitting pattern and a recipe for chutney with Rose, and Rose loaned the Swans sundries such as baking trays, clothes pegs and a tin bath.

But the relations between the families gradually soured. The Swans kept rabbits and the Goodings complained about the stench, and the Swans grumbled about the Goodings’ overflowing bin. When Ruth bore a third illegitimate child, matters came to a head. An animated exchange littered with profanities was allegedly overheard by Edith, with Rose accusing Bill of fathering the new baby. It was, maintained neighbour William Birkin, ‘the filthiest language I had ever heard.’ Believing that Rose was mistreating the new baby, Edith reported her to the NSPCC ¬ and that’s when it started.

The same obscene language that had been heard over the garden fence appeared in a litany of libellous postcards and letters delivered to Edith, and all those who knew her, and signed with the initials R.G. ‘You bl**dy old c*w, mind your own business and there would be no rows,’ said the first one. The language would amplify over time, becoming increasingly eccentric. Edith was a ‘foxy a*s p**s country wh**e’, they wrote, and her neighbour wanted ‘f*****g in the nose’. Though the notes appeared to be signed by Rose, who had a clear motive for attacking Edith, she insisted on her innocence throughout. It would take four trials, and the intervention of a plucky policewoman, Gladys Moss, before the culprit was unmasked and justice was finally served.

The true story behind these malicious missives is now the subject of Wicked Little Letters, which was released in UK cinemas on 23 February, and stars Olivia Colman as Edith, Jessie Buckley as Rose, and Anjana Vasan as Inspector Moss. The comedy, produced in combination with Studio Canal, Film 4 and Blueprint Pictures, is the first feature film produced by South of the River Pictures, founded by Olivia Colman and her husband Ed Sinclair.

‘Jonny Sweet’s script had us hooked from page one,’ the couple said in a joint statement released by Studio Canal. ‘He has a superb eye for ridiculousness and pomposity in his characters, and his background as a stand-up comic lends a real zing to his writing.’ Director Thea Sharrock said the story was ‘as relevant today as it was 100 years ago’, while producers Graham Broadbent and Pete Czernin of Blueprint Pictures said it shows ‘three heroic women ahead of their time, who bravely withstood the judgement of their community, and fought to be heard when the world didn’t want them to speak.’

At the time of the trials, illiteracy was still commonplace, with women like Rose and Edith only the second generation to benefit from compulsory education. The written word gave ordinary people access to knowledge and the power to represent themselves, but it could also be abused to spread hate and cause widespread harm.

In his 2017 book The Littlehampton Libels, Chris Hilliard delves into the social context of the tale. ‘The conflict broke along the divisions between established residents and newcomers, between respectable families and those with damaging secrets,’ he writes. ‘At a time when paid work and the credit needed to keep a household afloat depended on maintaining a ‘good name’, the libellous letters played havoc with reputations. The question of who made a credible witness before the courts likewise turned on the capacity to project respectability.’

From a lower social class than Edith, and, as a single mother, deemed to be a woman of loose morals, the hot-tempered Rose was judged most unfavourably by the law. When Edith launched a private prosecution against her, she was like a lamb to slaughter.

Edith, for her part, had little difficulty in having her testimony believed. In his 1946 memoir Criminal Days, Travers Humphreys, the barrister acting for the prosecution in Rose’s second trial, described Edith as ‘the perfect witness’, adding that she was ‘neat and tidy in her appearance, polite and respectful in her answers.’

In December 1920, following a 12-week period in custody as she could not afford the bail, Rose was sentenced to an additional 14 days in prison for criminal libel. Residents breathed a sigh of relief as the dirty libels ceased, but on Rose’s release, they reappeared as flagrantly as ever in the homes and workplaces of the local community, full of shocking sexual language and spiteful rumours that left chaos in their wake.

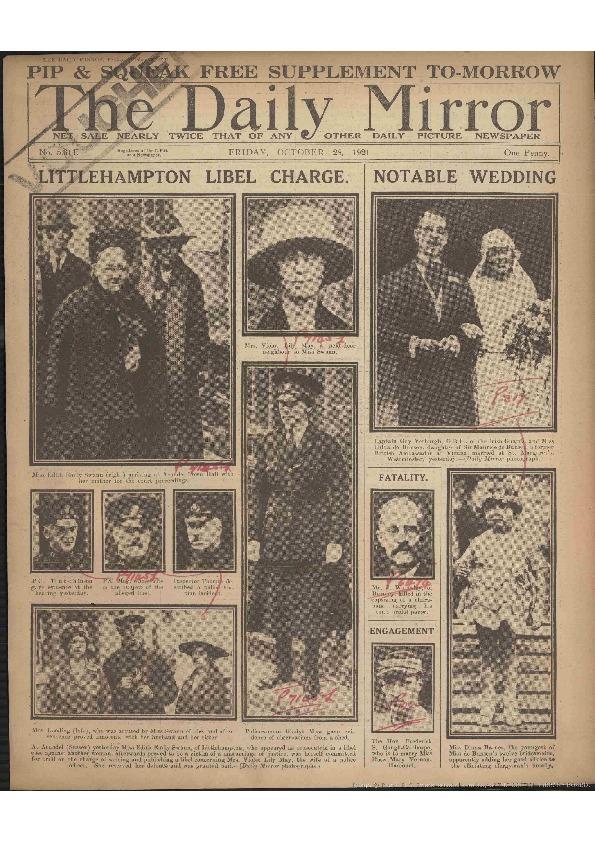

The Littlehampton libels’ long campaign saw Bert temporarily break off his engagement with Edith after receiving a letter claiming she was pregnant by a local policeman, and Edith’s livelihood suffered when defamatory notes were sent to her laundry clients. Still Rose insisted she had no part in it, but on 3 March 2021, she was found guilty for a second time and was sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment.

In a legal system dominated by blinkered officials who refused to investigate the handwriting of either defendant or plaintiff, it took a bold woman, police inspector Gladys Moss, to cast doubt over this trial by reputation. She installed herself in a garden shed in Norfolk Road which overlooked Rose and Edith’s shared yard, providing the perfect cover for a stakeout. By the backdoor of Violet May, a neighbour who had already received at least one libel in her peg bag, Moss observed someone drop a piece of paper penned with the same quirky vitriol. From whose hand did it fall? The shocking truth is the vulgar letters were from the plaintiff herself: the prim and proper Edith Swan.

When Edith stood trial at Lewes Assizes, she played her part well, dressing modestly in dark colours embellished only with a white chrysanthemum. The judge believed this respectable woman incapable of such vile language. Edith walked free and the nasty notes persisted.

But with national newspapers still gripped by this gritty drama, the police felt under pressure to solve the crime. Convinced that the guilty party had once again slipped the net, they launched a sting operation to fuel the investigation with additional evidence. A periscopic mirror was installed in the post office’s mail drop and stamps sold to Edith Swan were marked with invisible ink.

Edith’s compulsion to write the nasty notes, most likely the result of serious mental illness, meant that she was soon caught red-handed. Despite her protestations that ‘never during my whole life, either in writing or talking’ had she used such squalid language, she was finally found guilty of the libels and sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment with hard labour. Mr Justice Avory, still confounded by the mismatch between evidence and reputation, accepted the jury’s decision but stated: ‘It’s not my verdict’.

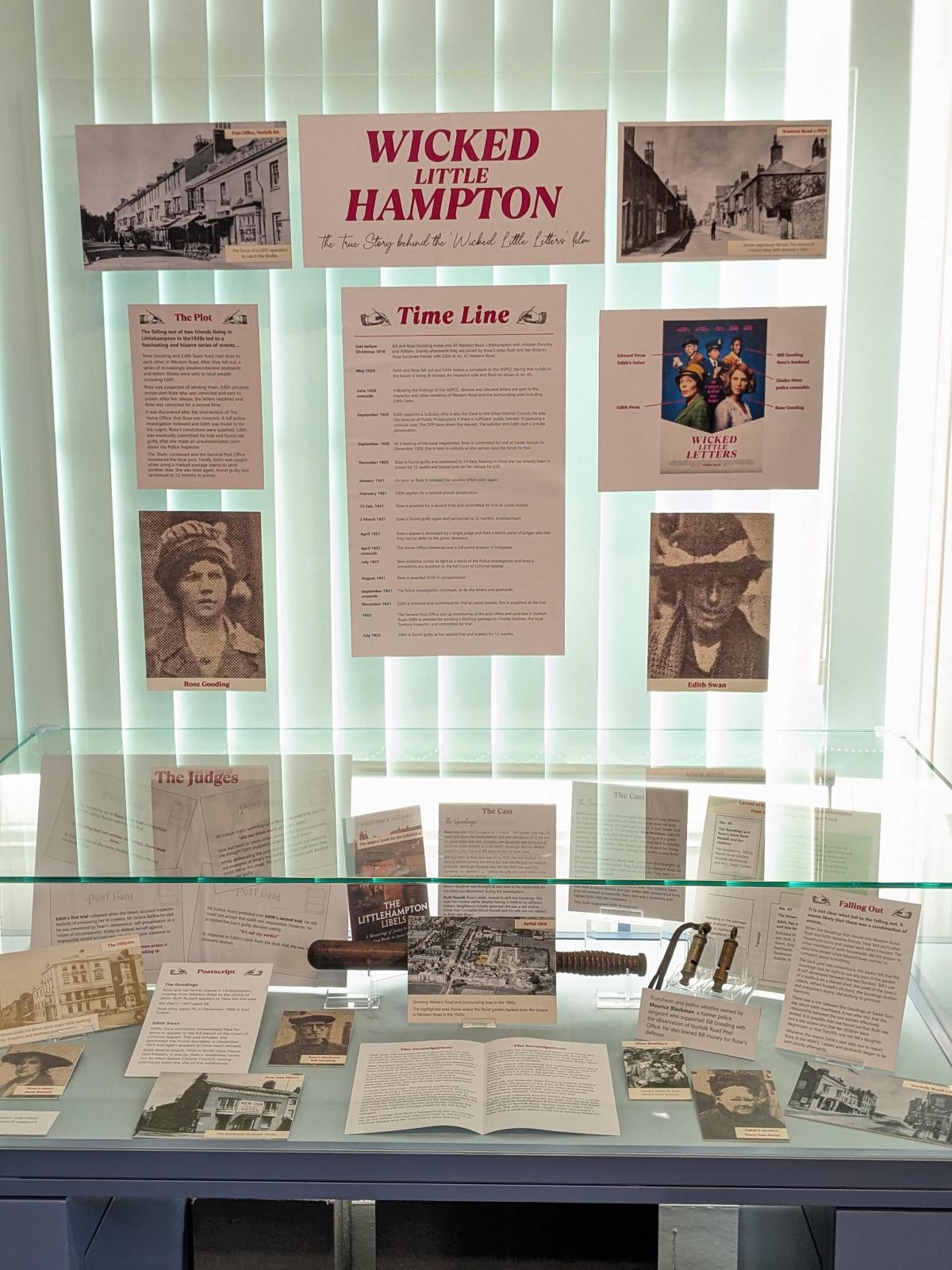

You can see photographs of some of the real-life characters and even read some of the scurrilous letters at Wicked Little Hampton, a micro-exhibition at Littlehampton Museum, but you’ll have to be quick as it’s only open until 26 March. The museum has also created a ‘libel trail’ of ten locations around Littlehampton that are key to the story, from the spot on Norfolk Road where Gladys Moss observed Edith at work, to the Urban District Council Offices on Beach Road, where Rose and Edith’s first magistrates’ hearings took place.

The filming of Wicked Little Letters has also taken the key characters further afield, with cast and crew spotted in Arundel town centre and on Worthing’s seafront. While 1920s Sussex was shocked by Rose’s potty mouth and Edith’s graphic turns of phrase, the modern-day cast have found the filthy vernacular fascinating. ‘I’m not a million miles away from Rose,’ Jessie Buckley told movie magazine Empire. ‘I love swearing and I could definitely relate to her.’ Colman has even framed one of the saucy libels in her loo. ‘I just love it,’ she said.