The propagandist has museums, pubs and paintings in his honour - but just who was he?

Lewes has many claims to fame: its riotous 5 November celebrations; Harvey’s Brewery; the imposing Norman castle of 107; Anne of Cleves’ House; even the worst avalanche in British history.

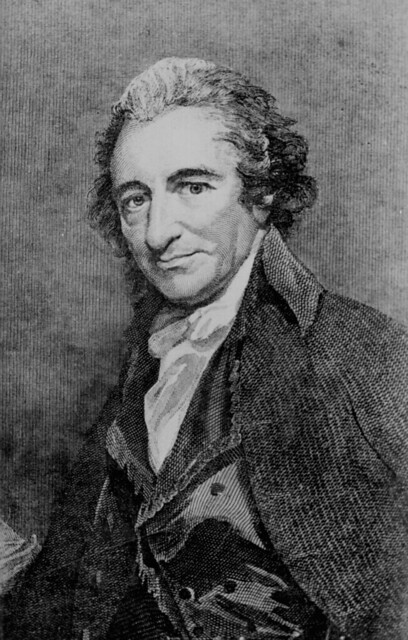

But ask any local who they consider its most celebrated past resident to be, and they will not hesitate to name Thomas Paine. A statue of him stands outside the library, his portrait adorns the town’s bank notes and there’s a mural painted in his honour in Market Passage.

One of the pubs - The Rights of Man - is named after one of his publications, and there are guided tours of his home, Bull House, in the High Street, at various times throughout the year.

And all this is just in Lewes. There are monuments and memorials to him across the world, particularly in America and France. There’s a whole museum in New York dedicated to his memory.

So who was Paine exactly, and what did he do that took him to such giddy heights of fame?

Thomas Paine hailed from Thetford, Norfolk, and originally worked as a rope manufacturer, then a schoolteacher. His father was a Quaker, his mother Anglican and his first marriage ended tragically when both his wife and child died during childbirth.

The move to Lewes in 1768, where he worked as a customs and excise officer, would prove a turning point in his life. He was so infuriated - to put it mildly - with the pay and conditions he had to work under that he published a lengthy pamphlet airing his grievances and exposing corruption within the service. Unsurprisingly, this led to his dismissal.

Pamphlets were the preferred way for people to let off steam about issues at this time. Newspapers didn’t welcome lengthy, controversial articles from the public, and books had long lead times as well as being prohibitively expensive for most people.

Pamphlets could be run off quickly in large quantities and sold cheaply, rapidly disseminating whatever message the author wanted to bring to public attention.

Paine wasn’t, as far as is known, a particularly political man before coming to Lewes, but his complaints about his job were to light the fuse on a whole powder keg of issues and establish him as one of the most radical social reformers of the modern world.

In Lewes, he lived at 92 High Street, and married Elizabeth Ollive, his landlord’s daughter, in 1771, but the marriage didn’t last. A move to London in 1774, with just £45 in his pocket, led to a chance meeting with Benjamin Franklin, soon to become one of the founding fathers of the United States.

Franklin suggested that Paine could seek his fortune in America, still embryonic in its development and made up of 13 disparate colonies, all firmly under British rule but agitating for independence.

The idea appealed to Paine’s restless and mercurial nature and he settled in Pennsylvania, finding work editing a local magazine. He immediately set to work writing provocative articles, a notable early one completely demolishing the case for slavery.

He quickly caught the mood that was growing for self-government in the country and actively supported it. Early in 1776, he published a 50-page pamphlet called Common Sense which would startle not just America but the whole western world.

With huge conviction, it set out the case for America’s break from British rule and included wider polemics on the nature of liberty, justice and systems of rule. It sold thousands of copies - its effect was described as ‘incendiary’- and was tremendously influential.

Many found its arguments about being ruled over by a far away British monarch, particularly astute: “In the early ages of the world, according to the scripture chronology, there were no kings; the consequence of which was there were no wars; it is the pride of kings which throws mankind into confusion.”

His dismissal of Britain’s supposed benevolence towards America also resonated: “Common sense will tell us, that the power which hath endeavoured to subdue us, is of all others, the most improper to defend us.”

Many nerves were touched by its articulation, it fuelled the flames of dissent and the famous American Declaration of Independence was duly made on 4 July 1776.

Paine immediately followed up Common Sense with a series of Crisis Papers between 1776 and 1783, essentially setting out how the country might achieve its own political identity.

From the first of these came one of Paine’s most famous quotes: “What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as FREEDOM should not be highly rated.”

But independence wouldn’t come easily. Military conflicts with the British at places like Lexington and Concord had already taken place, with more to follow. George Washington, who would become the first US president, was a key commander in the army.

He was on the verge of defeat in December 1776 at a standoff near Trenton (later part of New Jersey), and to rouse his troops he had one of Paine’s texts read out to them.

Part of this went: “These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.

“Tyranny, like Hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.”

MORE: Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Sussex inspiration

Washington’s men (one of them being Alexander Hamilton, the leading character of the eponymous smash-hit musical), then famously crossed the Delaware River in a flotilla of small boats on Christmas Day, routing mercenaries fighting for the British.

This and subsequent victories were pivotal in British rule being finally overthrown in 1783 and Paine was hailed as one of the key factors of the whole process. John Adams (the second US president) would say that: “Without the pen of the author of Common Sense, the sword of Washington would have been raised in vain.”

Paine worked for America’s early revolutionary government, but again his agitated temperament and febrile manner saw a return to Britain and a new flurry of activity, supporting a very different revolt, in France this time.

The Rights of Man, published in 1791, clearly supported what would become the French Revolution. The work was considered downright dangerous in Britain, raising fears the country could be next on Paine’s hitlist. Accordingly, Prime Minister William Pitt (the younger) issued a writ seeking Paine’s arrest, but he was already on his way to France to promote his views in person.

Here he was warmly welcomed and soon elected both as a French citizen and onto France’s first democratic parliament, even though he spoke little French. Napoleon Bonaparte became an admirer, though Paine would later be disgusted at his dictatorial aspirations.

But while moderates, who were happy to simply banish the country’s monarchy, regarded him as an ally, others - those eventually behind the ghastly ‘reign of terror’ - saw him as an enemy, particularly Maximillien Robespierre, who eventually gained power.

To stem his influence, Robespierre had Paine arrested in 1793 and imprisoned in Paris. He narrowly missed being guillotined. Friends in the US, led by James Monroe - another future president - rallied round to get him released the following year.

Imprisonment left Paine weak and unwell. But despite all these incidents and drama, there was no stopping his fervour or prodigious output. His next pamphlet, The Age of Reason published in 1794, was another major work, seen as his most radical yet, mainly because it attacked organised religion - and Christianity specifically - seeing its authority as arbitrary and leading to discord: “Persecution is not an original feature in any religion; but it is always the strongly marked feature of all religions established by the law.”

For some he seemed to be becoming a serial revolutionary, swiping at any established institution, and the work saw him marginalised in America and his popularity wane.

One last fling, Agrarian Justice, in 1797, was years ahead of its time, denouncing the inequalities of private ownership and actually promoting a minimum wage for agricultural workers through taxing landowners.

He returned to America in 1802, surprisingly pretty much forgotten, dying in June 1809 in Greenwich Village, New York. It’s said there were only a handful of mourners at his funeral. He was buried at his farm in New Rochelle (a gift from a grateful nation), but ten years later, William Cobbett, the political journalist, had the bones excavated, planning to return them to England and give Paine a hero’s funeral.

But this fell through, and the bones were lost some where along the line, never to be recovered. The headstone on the grave quickly disappeared, with pieces broken off by souvenir hunters. It’s rumoured that Paine’s skull somehow found its way to Australia.

But Paine’s fame and legacy have only increased as time has gone on and many of his thoughts, reforms and quotations have modern-day currency which can be applied to 21st century issues.

Indeed, at his inauguration in January 2009, Barack Obama quoted Paine, as he had done many times during his electoral campaign: “Let it be said by our children’s children that when we were tested we refused to let this journey end, that we did not turn back nor did we falter; and with eyes fixed on the horizon and God’s grace upon us, we carried forth that great gift of freedom and delivered it safely to future generations.”

All this explainss why Lewes is obsessed with a man, reckoned to be, if nothing else, the greatest propagandist in history. Many who live in the town have inherited his passion for free thought and autonomy and these ideas are reflected in many events held in Lewes, such as its annual speaker’s forum and in groups like the Headstrong debating club and the Skeptics in the Pub discussion set.

It could even be claimed they’re a key element of the 5 November celebrations. Although he only lived there for six years, Lewes and its people are still headily and inexorably suffused by the thoughts and aspirations of the legendary Mr Thomas Paine.