Landlubber Sue Cade meets a father and son working hard to keep the tradition of wooden boat building alive

In a world obsessed with the need for speed, there’s something calming about a wooden boat. The varnished gleam of wood in the sunlight conjures images of The Wind in the Willows and a slower pace of life.

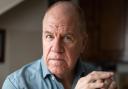

I’m in Axmouth to talk all things wood with boat builders Paul Mears and his son Alex at H J Mears & Son boatyard. The ‘H’ denotes Paul’s father, Harold, who founded the business in 1945 after learning the trade as a builder of wooden motor fishing vessels during World War II. The boatyard started life in Beer before relocating to Axmouth. It’s been at its current location at the harbour since 1982.

“We’ve just sold a wooden boat my father made that very year,” Paul tells me. “A chap from Taunton owned it for twenty years, sold it in 2003 and now it’s going to Warwick.”

Mears-made boats often come back home to be sold, as the boatyard is a magnet for wooden boat fans. “People just walk through the door in search of a wooden boat,” Alex says. “They love the look of the wood, and they know it handles better. Each boat is truly unique.”

The boatyard also produces modern, fibreglass boats; Alex explains that the yard wouldn’t survive on wooden boat production alone. It would be more profitable to switch over solely to fibreglass production, but money isn’t really the point; wood is the lifeblood of the business. For Paul and Alex, building a wooden boat is ‘simply a joy’, even if a labour intensive and gruelling one.

“We always like to have a wooden boat in build even when we don’t have an order. I keep threatening to get myself one. One of these days,” Alex chuckles.

A wooden boat can take 18 months to build. Alex and Paul build by eye, without drawn plans – they prefer relying on an instinct for the right lines from years of boat building experience. And although they do repair wooden boats, Alex says that restoration projects can be tricky.

“Often we start just to find that people have carried out their own DIY repairs or modifications. It’s down to us to make sure the boat is made right and seaworthy.” He points out a lovely old boat that even I can see would prove a heck of a challenge to restore.

I ask Alex which wood is best for boat-building. “Larch is probably favourite – it’s sustainable and locally produced. One of our boats in Lyme Regis, Hannah, is made from Devon larch.”

Paul adds that at one time boats were made from Brazilian mahogany, or a local favourite, wych elm. “But not anymore, because of Dutch elm disease. That makes it tricky for the Cornish gigs – the rules say they have to be built out of elm.”

Some boatyards work with ash or European oak to make the ribs which form the skeleton of a boat, but the Mears boatyard uses English oak. To make the ribs, the wood is bent in a steam pipe to create different angles and lengths. It takes four people to steam ribs and they have a 30 second window to get them into the boat while they’re still hot, using pre-drilled copper nails to fix them in place. Paul shows me a rib, and I’m impressed that you can bend a piece of wood like that without snapping it. “The grain has to be perfectly straight or the rib would break instantly,” Alex explains.

So, what type of person prefers a wooden boat over a sleek, modern fibreglass vessel? Alex thinks as well as the retired, younger people also appreciate craftsmanship and the appearance of wood.

Paul bemoans the loss of traditional boatbuilding in Devon. “There used to be three or four in Exmouth; those boatyards are flats, now.”

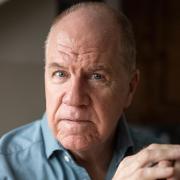

But there’s hope. Alex spent five years qualifying as a structural engineer and could have opted for a high-flying career.

Yet something convinced him that a desk job wasn’t for him, that what he did want was a more relaxed way of life maintaining his family heritage, and the sense of achievement from making something that would last. And there must be others who have a similar ethos, who will keep the traditions alive.

As I step on to a Mears’ boat, I feel I’ve made a step back in time, and I’m tempted to set sail under Axmouth Bridge and make my way out to sea. It would be a sad day if wooden boats were no longer launched from here.

Mears Boatyard favours use of wych elm timber for planking on boats – so why is it so good? Wych elm actually gets tougher with age in salt water as the timber gets pickled in the salt. It’s the fresh water from rain that will cause the rot to begin in planking. As a result, planking under the waterline will generally be sound for years while planks higher up that are exposed to rain water will need attention after 30 or so years. So a Mears-built boat doesn’t come with planned obsolescence like most overpriced gadgets nowadays, instead they build something you can hand on to your children.

mearsboatbuilders.co.uk 01297 20964