Spells and charms were part of everyday life during the time of the Pendle witches and their

legacy continues into the modern age, writes expert Joyce Froome

The death of eleven people in the Pendle witch-hunt is an enduring story. But it is also a window to one of the most mysterious and fascinating aspects of our past – magic.

The trial records make it clear that the people at the heart of the case, Elizabeth Demdike and her grandchildren James and Alizon Device, did practise magic. And other writings of the time can help us to fill in the details of exactly what this involved.

These “good witches” were traditional folk-healers, who used a combination of herbal remedies and magical charms. They were very important to their community, because most could not afford a conventional doctor.

James Device recited his healing charm to the Pendle magistrate Roger Nowell. It is 31 lines of eerily beautiful poetry, full of powerful Christian imagery, and includes a description of Jesus holding a wand blazing with magical power.

James would have spoken the charm over the person he wanted to cure, and then made the sign of the cross using a wand, a simple hazel stick cut from the hedgerow.

His grandmother, Elizabeth Demdike, was an even more respected healer, but her age meant she recited the charm over an object that could be taken to the sick person or animal – perhaps a sprig of the herb vervain, wood from a rowan tree or a cord knotted to tie the magic into it.

Elizabeth also asked James to go to communion but, instead of swallowing the bread, she was told to bring it back for use in magic. The communion bread was considered a powerful amulet against disease, worn round the patient’s neck, or put in farm buildings or even beehives to protect the animals.

The Pendle witches were devout Christians, but they also drew on traditions far older than Christianity. When James Device was arrested the constable found four human teeth that James had hastily buried nearby.Human teeth and bone were very important in healing magic. They were thought to contain traces of the life force of the dead person, and also to give access to the healing power of ancestral spirits.

Human teeth were worn as amulets against disease well into the 20th century, and the Museum of Witchcraft in Boscastle, Cornwall, has some beautiful rings carved from human bone that were probably used to treat rheumatism and arthritis. Magic was also used to discover the cause of an illness.

During the witch-hunts many diseases were blamed on witchcraft, so it was often the job of “good witches” to discover whether someone was ill because they had been cursed.

James’s teenage sister Alizon tried to convince the magistrate Roger Nowell that she was on his side, fighting against witchcraft just as he was.

As part of this plan she described how she had seen a witch performing a curse to make a child ill. This would have been a vision Alizon saw by gazing into a mirror, or a dream she induced by putting magical objects such as herbs and animal teeth under her pillow. However, there was another type of magic a teenage girl like Alizon would have been drawn to – love magic.

It often involved sticking pins into an apple or an onion representing the heart of the person you wanted to love you. It is probably no coincidence that the event that triggered the Pendle witch-hunt was a quarrel between Alizon and a peddler who refused to sell her pins.

But Alizon’s fatal mistake was to admit to Roger Nowell that she had a “familiar spirit” who took the shape of a black dog. Folk magic was closely connected to beliefs about fairies, including fairy animals like the Black Dogs who feature in legends across Britain.

The Cornish witch Anne Jefferies confessed that her healing powers were a gift from the fairies, and many “good witches” used magic healing stones they claimed the fairies had given them.

Unfortunately for them, King James I had declared that fairies were one of the shapes taken by the Devil – demonising some of Britain’s most deep-rooted folk beliefs.

To Alizon, her Black Dog was a spirit born of the wild power of the Pendle landscape. But to magistrate Roger Nowell he was a devil from Hell – and from that moment the Pendle “good witches” were destined for the gallows.

Spelling tests

Magic survived the witch-hunts and there are still traces of it in our lives today – in the horseshoes on our doors, and the black cats on our good luck cards. Perhaps you remember the old rhyme:

See a pin and pick it up,All the day you’ll have good luck.See a pin and let it lie,Sure to rue it by and by

It’s an echo from the days when pins were objects of magical power, and a quarrel over pins could start a witch-hunt.

The witch guide

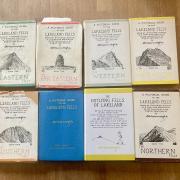

Joyce Froom is a historian at the Museum of Witchcraft and the author of Wicked Enchantments; A History of the Pendle Witches and Their Magic. Pictures: Courtesy the Museum of Witchcraft