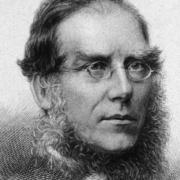

Fall and rise, rise and fall - it’s part of the human condition. Life’s snakes and ladders benefit some, such as TV's Reggie Perrin, and thwart others, like Mr Selfridge. Then there was Suffolk’s Thomas Wolsey, born 550 years ago in March, we believe. His rise was stellar, his fall akin to a lemming’s cliff tumble.

That self-serving king Henry VIII was fond of promoting fairly humble men. Having made them, he knew he could rely on them to serve his purpose. The long-established familial nobility he tended to eye with suspicion, never trusting further than his throw.

Wolsey (c 1473-1530), cardinal to be, was born the son of Robert Wolsey, a prosperous Ipswich merchant, and Joan Daundy. It’s not true he was lifted from the gutter - that ‘son of a butcher’ anecdote is disputed. He attended Ipswich School and Magdalen, Oxford, becoming a fellow and master in the foundation’s seminary.

Networking saw him become secretary and domestic chaplain to the Archbishop of Canterbury, then chaplain of Calais where his efficiency brought him to the attention of Henry VII, and he was duly appointed chaplain to the king in 1507. Handling the king’s private business with aplomb and skilfully undertaking embassies to the likes of Scotland obtained him the lucrative Deanery of Lincoln. Wolsey’s star was on the rise.

When Henry VIII acceded, Wolsey made himself indispensable to a young monarch more interested in hunting, jousting and chasing skirt than affairs of state. The king was happy having a trusted lieutenant to fuss over the dull stuff and Wolsey (or ‘Wulcy’ as he called himself) was energetic and self-assured as well as possessing a keen legal mind.

In the same year Wolsey became Henry’s Lord Chancellor, the top job, with more assets tumbling his way. By this time the unheralded bod from Ipswich wielded more power than any minister of the Crown since another Thomas - Becket - more than 300 years earlier.

Wolsey had a foreign policy and a domestic one. Abroad, he played off France and the Holy Roman Empire, hoping to make England the powerbroker. A Papal legate in 1518, Wolsey achieved his seeming great diplomatic triumph the same year, the Treaty of London. A show of peace between the Pope, the English and French kings, and the Holy Roman Emperor, it was followed in 1520 by the ostentatious Field of the Cloth of Gold, when Henry met the French king near Calais, an extravaganza orchestrated by Wolsey.

But ultimately, his hopes of ‘universal peace’ would prove as brittle as his hold on power. In 1521 England found itself at war with France again and Wolsey’s attempts to bankroll the conflict through an unpopular forced loan, the ironically named Amicable Grant of 1524, saw his popularity ratings plummet. At home, Wolsey was happy to allow Henry to play the role of absolute monarch while he profited as the power behind the throne.

In fact, he became the second most wealthy person in the kingdom after Henry and was dubbed ‘alter rex’ - the other king. His high living and haughtiness made enemies. But with new-found riches at his disposal, Wolsey turned benevolent as he began to plant his legacy. He was a great patron of the arts; he also established an Oxford college and a grammar school in his home town of Ipswich, where he had ambitions to create a future seat of learning.

Having scaled such heights, however, Wolsey’s fall was likely to be sudden and spectacular . . . and it was. The issue that brought Wolsey down was the so-called King’s Great Matter, or the thorny question of his divorce from wife number one, Catherine of Aragon. Henry needed to put Catherine away so he could marry Anne Boleyn, who would, hopefully, provide him with the male heir he needed. In 1527, Wolsey was tasked with delivering the Pope’s acquiescence to a divorce, but faced a pontiff who was unable or unwilling to act. Henry’s Great Matter turned into a drawn-out imbroglio of theological argument and counter-argument.

Wolsey failed Henry in his hour of need, his prevarication and evasiveness attracting the King’s ire. He also drew the latent hostility of the Boleyns and other malcontents who’d been waiting in the wings, biding their time. That time had come. Like a wounded animal, Wolsey was exposed and vulnerable. Suddenly the king’s protection was not assured.

In 1529, Wolsey was prosecuted under the Statute of Praemunire for having exceeded his papal authority. He was forced to give up the Great Seal, his symbol of Lord Chancellorship and high office, and retire from court. He was impeached by Parliament, his assets seized and forfeited to the Crown. The leviathan that had raised him up was now poised to bring him down. Wolsey faced a charge of high treason, but was spared trial and punishment when he died at Leicester on November 29 1530, aged about 57. He was on his way from York to London for what would undoubtedly have been the final denouement.

Among Wolsey’s last words were: "I see the matter against me how it is framed. But if I had served God as diligently as I have done the king, he would not have given me over in my grey hairs." Wolsey had served his monarch and, thereby, himself. Furthermore, this worldly cleric had a mistress for about a decade, Joan Larke, of Yarmouth, Norfolk, at a time when all priests were supposed to be celibate. He fathered two children before he was made bishop.

Wolsey's neglect of God would have wide repercussions. His unpopularity at the time of his fall resulted in reaction against the clergy which contributed to this country’s Protestant reformation. He was one of the last churchmen to play a dominating role in English political life.

Wolsey's timeline

c 1473 – Thomas Wolsey born in Ipswich (around March)

1507 – Wolsey’s rise to royal favour begins - he becomes chaplain to Henry VII

1515 – Henry VIII makes Wolsey his Lord Chancellor (until 1529)

1518 – Wolsey masterminds the Treaty of London

1520 – Wolsey orchestrates The Field of the Cloth of Gold

1524 – resumption of war, Wolsey’s Amicable Grant, his popularity plummets

1527 – Henry VIII tasks Wolsey with delivery of the King’s Great Matter, his divorce

1529 – Wolsey forced to relinquish the Great Seal and Lord Chancellorship

1530 – Thomas Wolsey dies in Leicester on November 29, aged about 57

Where is Thomas Wolsey?

Thomas Wolsey died and was buried at Leicester Abbey, although his burial site is unknown. The mighty sarcophagus he’d had built for his remains is in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral and is the last resting place of another prominent national figure, Admiral Lord Nelson.

READ MORE: Launch of Wolsey 550 to inspire Suffolk town of Ipswich