Refer to Jools Holland as a throwback to another era, and you’ll be paying him the greatest compliment. Katie Jarvis talks to the boogie-woogie band leader with old-world charm

Cornbury Music Festival: Friday, July 8-Sunday, July 10; plus touring dates in Oxford and Bath

‘Tell me about your paintings,’ is my Number One Question of Choice to Jools Holland.

I mean, he doesn’t paint (as far as I know) (I’ve googled that possibility in every word-combination I can think of, just to be sure).

He is a pianist extraordinaire; band leader, entertainer – every jazz aficionado’s dream; yet, also, the man to make anyone who doesn’t ‘get’ jazz stand up and cakewalk without need of a single sip of French 75 (champagne, gin, lemon juice, sugar; Stork Club, New York).

But I’m thinking back to The Tube, 1980s, Channel 4, scent of pheromones flooding the airways. Paula Yates – skin-tight leather one day; Dolce & Gabbana lace and rabbit-fur the next – quizzing interviewees about sex (once she swore so much on the studio floor, the crew threatened to strike); Jools steering conversations towards music.

%image(15712545, type="article-full", alt="Paula Yates with Jools Holland, Channel 4's The Tube, 1982")

Elton John, Paul McCartney, George Michael. All, at different times, flown up to the Tyne Tees studio.

Then Miles Davis.

Miles Davis, great jazz icon.

This is TV: short, snappy, flibbertigibbet-y. So keep the interview to one minute, Jools is told.

One minute? One minute? For one of the most influential music legends of the 20th century?

OK, two.

Oh. And another stipulation. Miles Davis wants to promote his paintings.

So the live interview begins, and Jools compromises: ‘Do you connect music with painting?’

‘Y-e-h,’ Davis says, pausing, evaluating, reflecting. After an eternity (one minute, 55 seconds, to be exact), Davis lands on his one answer of the entire interview. ‘Y-e-h. I would relate the two, most definitely.’

‘I was happy to stick to that subject [painting],’ Jools Holland writes in his memoir, Barefaced Lies and Boogie-Woogie Boasts, ‘since it’s always very difficult to talk about music.’

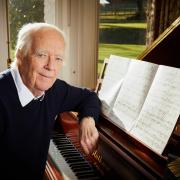

%image(15712546, type="article-full", alt="Jools Holland")

PAINTING’S out, then.

*Thinks hard* So let’s flip this round. What would Jools Holland – interviewer of stars – ask Jools Holland?

‘I like that,’ he muses. ‘I suppose it would be: What is the music that you really love? And I suppose it changes every day.’

(Why didn’t I think of that…)

Classical, rock ’n’ roll, blues, ska. Right back to the first recorded Do-Re-Mi. ‘It adds up to the same thing, really; it’s all about having an effect on the human spirit.’

I love that eclecticism. That desire to listen to everything. But what would Louis Armstrong make of Lady Gaga? Bach of the Beatles?

Jools Holland gives a sideways answer. Great artists are often… ‘Difficult is the wrong word. Challenging personalities.’ Take the Empress of the Blues. ‘If you had somebody like Bessie Smith come back now, she really would be a handful. She wouldn’t get very far if she went on the Voice. If they tried to offer an opinion, she’d tell them all to get lost.’

(He’s a great artist himself – no doubt about that – but he isn’t (in my interview) challenging in the least. He apologises four times in the space of three sentences (I counted) for changing the interview date a couple of times. I can’t give you an A-Z personality analysis as we’re talking by phone. Suffice to say, it’s as relaxed and friendly as a chat at Hogmanay.)

%image(15712547, type="article-full", alt="Jools Holland")

Lockdown has given him loads more time at home (in lieu of the usual diary inked black with touring); an opportunity to plug in outsize speakers and listen to stuff he probably wouldn’t otherwise have stumbled across. Cecil Gant, Brahms’s Ein deutsches Requiem. ‘I started to learn a bit of Bach, which I didn’t know before. I enjoyed doing that. And I listened to a bit of Celeste as well because I really like her voice.’

Gregory Porter once paid Jools the ultimate compliment. A throwback to another era, he called him.

What does Jools think he meant?

‘For me, that is a great compliment. For some people, it wouldn’t be – an old throwback. Like something you want to throw back…

‘But – as well as playing new things all the time, which is important - I grew up listening to a lot of old records and studying them. I liked the sound of them and I wanted to sound like them.’

The greats from the Jazz Age were mainly gone by the time Jools came on the scene. Even so, he’s played with a fair few, such as the idiosyncratically talented Slim Gaillard.

‘I remember Slim played with the [Jools’s] orchestra and he said, "You really do sound like people used to sound; I don’t know why it is." And I was very flattered by that.’

%image(15712548, type="article-full", alt="Jools Holland")

JOOLS HOLLAND and his Rhythm & Blues Orchestra are playing Cornbury this July; touring again this autumn/winter – with some of today’s greats joining some of those gigs: the aforementioned Celeste, Joss Stone, Lulu, Vic Reeves, Roland Gift; his old Squeeze (band-mate) Chris Difford.

It’s a tour showcasing Jool’s latest album, Pianola, Piano & Friends. And it features a star-studded cast: David Gilmour, Sir Tom Jones, Jamie Cullum, Gregory Porter, Joe Bonamassa, and Lang Lang are just some of those names.

There’s another, even older star, too. Because right at the heart of this album is an 86-year-old pianola. A battered, war-damaged instrument that would play music all by itself (courtesy of perforated rolls of paper: Red Sails in the Sunset; Christmas songs when the turkey had been ingested), with the family crowded into grandma Rosie’s 7 Hassendean Road, Greenwich, terrace: kitchen with scullery, budgie in a cage, flying ducks on the wall: ‘by far the loveliest place in the world’.

%image(15712549, type="article-full", alt="Jools Holland: ‘I remember Slim played with the orchestra and he said, "You really do sound like people used to sound; I don’t know why it is." And I was very flattered by that’")

It was on this pianola – WH Barnes, London – that an eight-year-old Jools Holland began picking out the songs he heard his Uncle David play in his R&B band, The Planets.

‘I’m not against what I describe as mumbo jumbo,’ he tells me, ‘but I’ve never seen a ghost or anything like that. I do think, though, old instruments have got some spirit about them. An old instrument that has been played a lot by somebody is worn by those fingers; you’re playing something a bit more than just the wood and the strings or whatever it is. I find that with old guitars I’ve bought; they definitely have a feel to them.’

He gives me a whistle-stop pianola tour: from its origins in the 30s – no TV; no computers; ‘If you were even modestly well off, you’d buy a piano’ – to the loss of the first of its nine lives.

‘In the Blitz, the front room where this piano was scorched out; the side of the piano is still scorched from that. Had it been four houses up, it would have gone.

‘And then there’s a picture of it after the war, when they brought it out when peace was declared on VE day, and it’s out on the street at a street party. You can imagine the celebrations - the frissons between men and women returning [from the war] – with the piano jangling in the background. What a story.’

Later, when Rosie had gone, Jools’s mum inherited it; she joined a pianola society, and collected more and more rolls: ‘She must have had 100: Jelly Roll Morton, Fats Waller; then you’ve also got some of the great concert pianists of the 20s and 20s, like Rubenstein.’

The pianola is in his house now. ‘And part of the lockdown was making friends with it again. The strange thing was, it had the same aroma. They say that the sense of smell evokes the greatest sense of nostalgia in people.’

Polish? A thousand roast dinners? Burning wood after a passing Luftwaffe? Whatever aroma it was, it took Jools Holland right back to the time when he’d play it obsessively, forensically dissecting the records he heard; musically putting them back together again.

‘My poor neighbours; my poor grandparents.

‘I mean, it’s an old banger; it’s never been restored. A lot of people would think it’s probably unplayable. Having said that, a piano is one of the few things you buy that will last you one or two generations and maybe even three or four. Most things, like a fridge or a car, you chuck them away – they don’t last…

‘I sound like a piano salesman.’

%image(15712550, type="article-full", alt="Katie Melua and Jools Holland at the European Border Breakers Awards, 2011")

THE INTERESTING THING about Jools Holland being a throwback – in the nicest possible sense – isn’t just the sound he makes. It’s the way he re-evokes that sense of community. The rightful place of the piano as the friend in the corner of the living room; the centre of the party; the Friday night in the Mitre by the Blackwall Tunnel: no ‘Live Sky Sports’ in the 60s and 70s; instead, there’d be Neville Dickie or Chris Barber; or Harry Gold and His Pieces of Eight, playing to the old dockers supping their pints through the smoky fug.

The album – and the tour – have something of a flavour of that time. So many collaborations between Jools, his orchestra, and invited musicians, where the alchemy fizzes with surprises.

‘On my piano record, I do a duet with Lang Lang; he, as a pianist, is the opposite of me. I’m kind of syncopated and jazzy, and he’s much more romantic… I don’t know if you know what I mean by that.

‘What comes out is something really great.’

Mind-blowing.

‘Because you’ve got one instrument and you think: How many ways can you play it? But when you hear that, you realise there’s a million ways to play it. And a million ways in the middle…

‘I sound like a piano salesman again.’

%image(15712551, type="article-full", alt="Right at the heart of Jools Holland's album is an 86-year-old pianola... this isn't it")

LET’S THROW IN some random questions in the few minutes I’ve got left. (None of them paint-based.)

Like how his memoirs detail, with grace and lightness, some pretty difficult times. Music has – at points – been not just his pleasure but his salvation, right?

‘Myself and Sam Brown wrote a song which Ray Charles was going to do – but, then, unfortunately, he died so he couldn’t - based on something he said. Which was: You can like my music, you can dislike my music, as long as you know when I write music I’m telling the truth because music is an extension of yourself.

‘Music has been incredibly good to me: I’ve seen the world; I’ve met some extraordinary people; I’ve been in places I couldn’t have dreamed of being in.’

No kidding. He’s met/worked with some extraordinary people. Not just musicians, either – Tommy Cooper; Reggie Kray.

Who surprised him most?

‘I met Reggie Kray the once. He wrote to me and asked me to visit him in prison, and that was pretty brief. The same with Tommy Cooper; I worked with him once but that was just very exciting for me because I’ve always liked him.’

Lucian Freud he got to know better.

‘What I wasn’t expecting was that the person Lucian loved most of all in music was Johnny Cash. He was very excited when the Man in Black appeared because he just loved it. He was very contrary, Lucian. Whatever you thought he would think, he would deliberately think the opposite.’

OK, so what about those artists he missed. Whose eras didn’t coincide.

Keys to a time machine. Where’s he going to go?

He thinks. There are so many times; so many places.

‘If you could go back to New Orleans in the 1920s, that would be pretty amazing; Kansas City in the 1930s; New York in the 40s. Those places, you would have heard the beginning of the greatest music; that would have been quite a thing.

‘I could have stood at the back of a theatre and heard Bessie Smith – I would have loved that. Or a dance hall and heard Count Basie with all the GIs. Hank Williams doing his thing. Or I would have loved to have gone to the British Music Hall and heard Leslie Sarony.’

Or gigged with some of the old jazzers. ‘When you hear what they’re doing, it’s so extraordinary. I don’t know if they’d have had me.

‘I would like to have heard Bach playing his own music. With the jazz stuff, it’s all recorded; you can hear what they sounded like, and there are films of people as well.

‘With the great classical composers, people say, ‘Oh, they wrote on their score what it’s supposed to sound like’, but you never really know. What tempo – what the feel was. I’d just love to have heard what the fellow himself did.’

Absolutely.

Or maybe just travel back to Hassendean Road to see weary, jubilant soldiers trooping home. And watching them dance to the jingle-jangle of a scorched piano.

%image(14516643, type="article-full", alt="Jools is appearing at this year\'s Cornbury Festival (July 8-10, 2022)")

Jools Holland and his Rhythm & Blues Orchestra will be playing at Cornbury Festival, July 8-10: cornburyfestival.com

Tour dates include Oxford on November 12 with Roland Gift; and Bath on December 8 with Lulu. Tickets are on sale via ticketmaster.co.uk / seetickets.com

More on Jools at joolsholland.com