Award-winning writer Jamila Gavin talks to Katie Jarvis about multiculturalism, the view from Rodborough Common and her Cotswold life. Pictures by Antony Thompson.

Jamila Gavin is a remarkable writer, whose books have spoken to children the world over about the difficulties and riches of multiculturalism. “I’m mixed race,” she says. “I had an Indian father and an English mother with very powerful connections to both cultures.” Her first book, The Hideaway, was born of a feeling of isolation, after moving from London to the Cotswolds more than 40 years ago. “Then, over the next 20 years, I went into a multicultural phase, before writing Coram Boy, which is my second real response to the Cotswolds. The first book was as a newcomer; the second was, ‘Surely I belong here now. Can I not claim it as mine as much as anybody else?’”

Coram Boy, of course, won the Whitbread Prize, as well as being adapted by the Royal National Theatre and making an appearance on Broadway.

Jamila’s latest public venture is a revival of Cider with Laurie, as part of the Laurie Lee Centenary Celebrations. A community event, the performance by Jamila and friends will feature readings and live music, celebrating Laurie’s life through his own words.

• Where do you live and why?

I live in a suburb of Stroud, along the Slad Road, in an area called Uplands. It’s a very calm, rather lovely place, with a real community of neighbours. My house is one of a terrace of three; every summer, we open up our gardens and hold a big party together. In my heart, I’m a Londoner: I was born in India but, whenever we came to England, it was to London. I had my secondary schooling in London; I was a music student in London; and I married in London. When I first moved to the Stroud Valleys - to Chalford - I did feel a sense of imprisonment, which I think one can put down to the geography of the steep valleys; I would get a feeling of freedom whenever I climbed to the top. But I went from feeling a prisoner to feeling terribly privileged. If you like, it’s an open prison – though I think I ought to dispense with the word ‘prison’! – because I can leave Stroud and I can come back. The leaving is like a bird taking off and the coming back is like a bird returning to nest. It is very much home now.

• How long have you lived in the Cotswolds?

Since 1970. My husband and I moved here, realising we could live so much more cheaply than in London, yet still get there easily on the main-line. It was a period when places like Stroud were attracting people looking for alternative ways of living; people escaping from the cities and finding a real soul-connection with the beauty and peace of the valleys round about. Stroud is not pretty, as such; it’s never going to be one of those high-value places, such as Painswick. But it has an unpretentiousness, which I particularly love.

• What’s your idea of a perfect weekend in the Cotswolds?

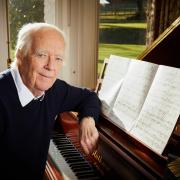

It would definitely be walking: I love the common; I love the woods - though I have to make myself go out instead of sitting at home, writing all day. (All writers feel guilt if they’re not stuck at their desks!) My perfect weekend would have to include my piano, too: music is the air I breathe. My mother wasn’t one of those pushy, ambitious parents, but she clearly thought my path lay in being a concert pianist. And I was certainly on track – I was a junior exhibitioner at Trinity College of music; I got a scholarship to Paris; but I suffered hugely from nerves from the age of 16 onwards. My generation was producing Barenboim and Martha Argerich, and I was never going to be one of those. In the end, what always kept me practising eight hours a day was my sheer love of music. I go through great phases of playing Bach, Schubert, Mozart, Beethoven, and a friend and I play duets together, which is wonderful.

• If money were no object, where would you live in the Cotswolds?

I love where I am and don’t yearn for another Cotswold home but, if I won the Euro lottery, I would buy a house in Holland Park: I love the long, leafy Bayswater Road, and then you’re so close to the parks, which are the great wonder of the capital. What takes me to London now is family – my daughter and son and their families live there. But, nowadays, funnily enough, if I was told I couldn’t have both – London and Stroud – I think I would probably choose Stroud, as indeed I have. It’s the longest I’ve ever stayed in any one place.

• Where are you least likely to live in the Cotswolds?

In a deep dark valley that doesn’t get the sun for six months... A lot of people might say Stroud – and I do sometimes feel as if Stroud itself doesn’t recognise its own value. It allows some pretty grubby development, where I wouldn’t chose to live. I sometimes think they slap houses in like typewriters – a keyboard of houses, all the same, around the hillsides. That distresses me.

• Where’s the best pub in the area?

I love the Woolpack, just down the road in Slad; the Black Horse in Amberley; and the Daneway, where we used to go a lot as a family - I adored those walks along the canal.

• And the best place to eat?

I use Star Anise a lot [arts café in Gloucester Road, Stroud]. I really feel at home there. And we are so privileged to have HK House, one of the best Chinese restaurants I’ve ever been to, either in or out of London.

• What would you do for a special occasion?

Go for lunch at the Woolpack with lots of friends, or to Stratford to the theatre. Certainly, a highlight of my career so far – which was a very special occasion - was seeing Coram Boy at the National. I could hardly believe it was me it was happening to. It was an extraordinary process, bringing it from page to stage, and I had to gulp hard at seeing another writer adapt my book: there was a lot in the dialogue and in the approach that at first I really struggled to come to terms with. But when I went to that first night, I was completely bowled over. And it was stuffed with music from beginning to end – all the actors had to be able to sing - which was a complete confluence of everything I’ve loved all my life: music, theatre, story-telling, writing. It briefly had a Hollywood option but Alan Parker demanded such a colossally high budget – almost a small country’s GDP – that it didn’t happen! Now the BFI has got involved and it is being worked on. I’m waiting to see a script and to feel that terror again of seeing my book going into someone else’s hands.

• What’s the best thing about the Cotswolds?

Its beauty. My mother loved the Cotswolds: one of my earliest memories is of her pointing west, when we were in India, and saying, “England is over there!” She came from Staffordshire and passed her really visceral love of the English countryside on to me – I got it through her story-telling; through the kind of poems she read to me – Shelley, Tennyson, Wordsworth. It was she who brought us here, by buying a house in Avening. Her fantasy was always to live in rural England.

• ... and the worst?

I don’t feel at this stage in my life that I can be negative about anything, though I do regret that many schools are not seeing multiculturalism as something they still need to attend to. My writing has constantly reflected the black British - meaning non-white - experience. I have been into primary schools – particularly in country areas – where there are no non-white faces. Mistakenly, teachers would shrug and say, “It’s not a problem for us”; and I’d reply, “But when your children leave you and go to a comprehensive – in Gloucester or Bristol – they are going to start meeting multicultural Britain and they need to be prepared for it; they need to understand it.” I’m not in favour of faith schools, though I can see the reasons why they came about. Nevertheless, I feel the concentration should have been on really super secular state schools, with a strong multicultural and multifaith component, where children not only learned about each other technically but mixed with and understood each other in the playground.

• Which shop could you not live without?

Mother Nature [in Stroud], and Waitrose where I load up my car once a week. I’m always going to the Coop – it’s an absolute blessing – as well as the [Uplands] post office. We were all horrified when the post office’s existence was threatened: thank goodness for Stroud Town Council, a great promoter of localism. When people sit in planning offices with their sheets of paper, those sheets are flat. They don’t reflect the steep hills and valleys and dales that people have to struggle up and down. Planners promote getting away from the motorcar for the environment; but they also need to make sure we have facilities within walking-distance that are accessible by older people and by mothers with prams.

• What would be a three-course Cotswold meal?

It would be partly vegetarian – I think of the wonderful meals at Star Anise - but then I can’t help thinking about Old Spot sausages and mash. So it would be halfway between good old comfort food on the one hand, and lentils, salad and pitta bread on the other!

• What’s your favourite view in the Cotswolds?

Standing on top of Rodborough Common by the fort and looking across to the River Severn broadening out towards Bristol: the way the light changes; the way the hillside winds round like a wrinkled forehead with those funny little tracks, and the woods below.

• What’s your quintessential Cotswolds village and why?

I’ve never wanted to live in one of these pretty-pretty villages. It would feel like too much of a responsibility to conform to an ideal and I’m not sure that ideal is real. Chalford, however, is very real. It feels so lived in: people are visible – walking along the streets; digging their gardens; walking their dogs along the canal that runs through. One of the first books I wrote – The Hideaway - was not inspired by my multicultural background but as a direct response to my feeling of having newly-arrived into the countryside and being an outsider; loving its beauty but feeling unease with it.

• Starter homes or executive properties?

We can’t have the pretty little villages any more but we can create our estates with much more imagination, not just build soulless housing developments. I hate saying that because I do know people who have moved into some of those houses, and they make them beautiful; they value just having a roof over their heads.

• What’s the first piece of advice you’d give to somebody new to the Cotswolds?

Transport is a real issue, and people need to know what their values are about driving. When they’re thinking about where to live, they should ask themselves all sorts of questions. Have they got children? Are they elderly or with an infirmity or disability? Where is their nearest shop? Can they just pop out to buy milk or bread? Access is one of the most important things to take into consideration.

• And which book should they read?

Laurie Lee had such an ear and an eye: he was a painter; he was a poet; he was a musician; and all those things are reflected in his words. Cider With Rosie is not a campaigning book; he’s not saying, “You’ve got to read this book because you’ll learn about history or what it’s like to be poor”. It’s pure observation and involvement in his experiences as a child growing up in the valleys, and his need to get away, which he did. And Laurie coming back at the end of his life is something I think many others will feel in their bones. I didn’t know Laurie but I was once at a dinner table with him and was intrigued to find his story-telling was an exact reflection of the way he wrote.

• If you were invisible for a day, where would you go and what would you do?

I’d love to be invisible to the foxes, badgers and the birds, so that I could watch them properly. The sparrow population has declined over the years, and I haven’t heard a cuckoo or an owl for a while. Once upon a time, you’d hear those owls hooting each evening in the church up the road.

• To whom or what should there be a Cotswolds memorial?

I mourn the fact that we didn’t get our act together when Lynn Chadwick was alive and commission a statue for Stroud. It would also be fantastic, and totally appropriate, to have a statue of Laurie Lee.

• With whom would you most like to have a cider?

I’d love to have met Mozart and taken him to the Woolpack. He had such a humanity and a wit, and I wouldn’t have been daunted by him in the way that I would have been by Bach or Beethoven. I also regret I left it too late to meet Rumer Godden. She was my kind of writer.

-------------------------------------------------

Cider with Laurie - on tour, the story of Laurie Lee’s life told through his own writings, edited by Jamila Gavin, visits the Museum in the Park on September 21 and and Kingshill House, Dursley on October 4. Tickets are £8, including a complimentary drink. Booking necessary on 01453 760960 (01453 549133 for Dursley).

Jamila Gavin’s latest book is Blackberry Blue: and Other Fairy Tales. She also contributed a short story, The Man in Red Trousers, to Tony Bradman’s anthology Stories of WW1. For more about her work, visit www.jamilagavin.co.uk