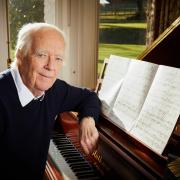

Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen says it’s time to stop denying ourselves life’s pleasures; what we really need is more, more, more

Words: Candia McKormack; photography: Steve Thorp

‘I’ve known about this place for such a long time,’ says Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen, as we sit chatting in one of the welcoming rooms of The Dial House hotel in Bourton-on-the-Water. ‘It’s a Cotswold jewel box... but the thing I found most enticing about it was that it’s basically my house.’

Ah, Roberts House, Siddington – the beautiful 17th-century haunted home of the Llewelyn-Bowen dynasty, with dreamy gardens tended by Jackie, and interior designs by LLB himself – that the family moved into 15 or so years ago, famously captured in the TV series To the Manor Bowen. ‘Aren’t we a little bit too rock ‘n’ roll for somewhere like this?’ says Laurence in the first episode, sitting on the back seat of the family car with daughter either side and spaniel on lap. Ah, but no; they brought their own brand of Metropolitan-chic rock ‘n’ roll to the Cotswolds and discovered that, actually, Gloucestershire has its own avant-garde, decadent side... we just don't like to let too many people outside the area know about it.

Laurence has, of course, gifted quite a few public buildings in the Cotswolds with his design magic, but when he was approached to do the Bourton job, he initially had his reservations.

‘I’m afraid to say I was a bit feisty about it at first as I’m just so bored of all the Cotswold clichés; the greeny-grey do-not-look at-these walls and the contemporary furniture, with everything feeling a bit uncomfortable... a little bit puritanical. The thing that’s wrong with Cotswold hospitality is not the hospitality – which is wonderful – it’s the hospitality context, which is frankly Roundhead. There’s something Cromwellian about the contemporary Cotswold style, with its understated style and rickety modern furniture.’

But, if we’ve all become comfortable with being uncomfortable, what’s a designer to do?

‘I wanted to make a very strong link between the Cotswolds and the Arts and Crafts movement,’ he continues. ‘It was people like Ashbee, Owen Jones, Walter Crane – and we all know about William Morris, of course – who all used the Cotswolds as a real springboard for all that we love about the movement; its chunky integrity and ‘Britishness’.’

And so, what he’s done at The Dial House is to create a series of suites based around his heroes of the Arts and Crafts movement: Oscar [Wilde], Owen [Jones], Walter [Crane], Aubrey [Beardsley], and May [Morris]. ‘I didn’t want to do William Morris,’ he says; ‘he’s great and all that stuff, but May – who took over the business after he died – is a real unsung hero of the movement. Of course, Hermione [Jackie and Laurence’s daughter, who’s an integral part of Llewelyn-Bowen Design brand] loves this and already has her sights set on the iron throne!’

The idea was to revivify the Arts and Crafts movement, as it existed from 1880 to 1930, but for a completely new millennia. ‘It’s such an indelible part of the British aesthetic psyche,’ he says, ‘I think it can and should be used to lead into a completely new way of decorating.’

Laurence says it’s become an ‘informal mission’ of his to turn the Cotswolds into the Capital of Maximalism, and a part of that vision was opening a tipi – ‘Maxi’s’ – in the garden of The Dial House. Essentially, wanting to create a ‘giant pillow fort’, he designed a bespoke pattern for the hotel – called ‘The Dial House’, naturally – which has been used in the tipi, but which will also eventually be inhabiting the restaurant, bars and other public areas.

Anyone who stays at the hotel and wants to attempt to recreate the feel of it in their own homes is in luck, as Llewelyn-Bowen Design is launching The Dial House furniture collection, based on pieces he’s designed for the rooms. It’s a similar ethos to the (very welcoming) environs of the LLB showroom on Cirencester’s Castle Street, where everything you see – from the vases and candles to the wallpaper and soft furnishings – can be bought. Not only that, you can also choose which of Laurence’s opulent designs you adore most and have it laser-printed on the fabric of choice at the exact scale to suit both your home and your very discerning taste. Quite brilliant.

‘There was a time – up until Covid,’ he continues, ‘that travel was incredibly important to the way people decorated, and the boutique hotel experience influenced how we wanted our homes to be. And so, closing that circle by doing it up here was a very straightforward thing to do.’

Discussing Laurence’s latest book – More More More: Making Maximalism work in your home and life – leads us onto Seventies disco (remember Andrea True Connection’s breathy soft-porn classic?) and how, he believes, disco is the ultimate in Maximalism. The book itself, though, is far more lovely. On first glance, the gorgeously playful, strokable hardback book appears to be a Monty Python-esque collage of LLB’s most feverish of fever dreams... but curl up fireside with a mountain of über-velvet cushions to give it the attention is so deserves, and you’ll find it’s a well-researched, filthily irreverent global journey through the history of art, taste and style.

‘I’ve always wanted my design to be like an afternoon with Google,’ he says, ‘that takes you off into all sorts of places. Maximalism has almost sprung up overnight; it’s a slightly unwieldy term for what is, essentially, anti-Modernism. All of those rooms that cost a fortune to heat; all of those echoey acoustics and uncomfortable furniture... what were they there for? What was that about?

‘My journey through the book is challenging why people believed that was a good idea; why did we want to control life like that when we could have been surfing it instead? Minimalism in any other context is death. A minimalist plant is a dead plant. Minimalism is poverty. To conspicuously consume emptiness sounds like some weird Oscar Wilde fable gone wrong.

‘From lockdown we got this enormous explosion on social media of people who had bought navy blue paint on the internet, got Granny’s china out of the understairs cupboard; all the things they’d denied themselves because they didn’t want to be judged... suddenly they wanted to be judged. Maximalism is the moment when the lunatics take over the asylum, and I love that. I’ve always been more lunatic than asylum-keeper.’

Conversely, Laurence believes Maximalism is, at its heart, anti-consumerism. Many people now seek out pre-loved on eBay or scour charity shops and second-hand markets, because they actually want stuff ‘with ghosts’.

‘The 20th century was a f*cking disaster for taste,’ he says. ‘By trying to make proletariat design over-intellectualised, nobody liked it. I have great fun taking the piss out of Bauhaus: this horrible, prescriptive existence you were supposed to have where you lived with shiny lino floors, crittall windows and one piece of uncomfortable furniture. The joke is that the moment you moved in, it became all antimacassars and floribundant wallpaper because that is humanity’s factory setting.’ He leans in and adds, ‘There was a condition called ‘Bauhaus breath’, you know; they used to have to eat a very high-fibre vegetarian diet – it was all very grim – and so they’d sneakily eat garlic between meals, just for something to eat.’

It does make you question the need to deny ourselves pleasure; imposing a kind of self-control that can only lead to misery. One of the things that Laurence has been exploring in his new series for Channel 4 – Outrageous Homes – where he visits people who have never worried about what the neighbours think or what the estate agents are going to say.

‘They live as vampires,’ he says, ‘with film on the windows to not let the sunlight in; they’ve given up half their room to a fish tank which they then get into with the fish; they paint everything in their world only pink or yellow. There are 16 of them so far, and these people are absolutely extraordinary because the one thing they have in common is that they’re all happy. This is what’s really good about Britain; we’ve always really liked people who are a bit different.

‘I say in the book “Never be a class; they’re all ghastly”; if you’re going to be a class, make up your own, because the ones we’ve got are rubbish! I’m not by any means wanting to put myself onto a soapbox – obviously it’s wry, and obviously it’s a piss-take – but essentially the book is a series of essays that asks why we do what we do.’

Earlier this year, BBC2 aired a series called Pilgrimage where Laurence and six other ‘personalities’ with differing faiths and beliefs followed ancient trackways – from Eire to Iona – tracing the roots of Celtic Christianity. In the series, Laurence states that ‘I’m happy for there not to be a God’, and that he identifies as a ‘non-conforming pagan’.

‘I’m very moved by people’s faith,’ he says, ‘it’s a beautiful thing. I also get very moved by the historical accretion of faith. Our churches which are so very old and so very beautiful were created by generations of people – there were no short-cuts – and then their descendants went there and sang, worshipped and read poetry. That moves the hell out of me. I don’t need God in that; the people are more than enough.’

Just when you think you’re getting a handle on what makes LLB tick, he’s here to surprise and to make us question why we do what we do... and I think we could all do with more of that.

Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen's More More More is published in hardback by Dorling Kindersley at £20.

Llewelyn-Bowen Design, 42 Castle Street, Cirencester, GL7 1QH, llewelyn-bowen.co.uk

The Dial House, Bourton-on-the-Water, GL54 2AN, dialhousehotel.com

Outrageous Homes is due to be screened on Channel 4 in January 2023.

*******

DESIGNS ON THE DIAL HOUSE

I’m taken on a tour of a couple of the LLB-designed rooms not currently occupied, and they’re a delight – each with its own personality, reflecting that of the Arts and Crafts great it’s dedicated to. All include some of the original sketches and early plans for the rooms so you can see Laurence’s thought processes, and everything you see has been designed specifically for the room, from the book spines behind the bed in ‘May Morris’ (created by Laurence’s son-in-law Dan), to the golden sunflower-strewn wallcoverings in ‘Oscar’, and the exotic bird-inhabited piped cushions in ‘Walter’.

Here’s a summary of the rooms in Laurence’s own words...

May Morris

‘My homage to William Morris’ daughter, who took over the business after he died. She has incredibly strong Cotswold roots. She, I feel, took Arts and Crafts into a very 20th-century direction; she turned the colour palette up and made the designs that little bit more ‘bombastic’. I wanted to create a space that had all of the enjoyment and energy that the Morris dynasty derived from nature.’

Walter

‘Based on English artist and book illustrator Walter Crane, this is an indulgent and quite extravagant evocation of bird-and-bough pattern-making, with fantastical feathered friends, lending it a ‘boudoir’ feel.’

Aubrey

‘This is based on the personality of illustrator and aesthete Aubrey Beardsley. Very much a figure in the Arts and Crafts movement, but rather at its floppy, decadent end. The room is very much trying to evoke his very keen sense for interior decoration – he was very keen on dark colours and emphatic gestures. The bespoke tapestries bring the room together, and it’s been very popular with brides who see it as the ideal matrimonial environment... goodness knows what stories those tapestries can tell.’

Oscar

‘This room is based around a design of repeating sunflowers which I think he [Oscar Wilde] saw as a symbol of himself. Gilbert & Sullivan took the piss out of him and the aesthetic movement with Patience, and in fact the wallpaper in ‘May Morris’ is called ‘Down The Dilly’ because it features a tulip and a lily; in the aria that Bunthorne sang, he walked down Piccadilly, ‘with a tulip or a lily’.’

Owen

As a Welshman, I’ve always had such a huge soft spot for Owen Jones. He was involved quite early on in the Arts and Crafts movement, and became a walking encyclopaedia of decoration. The Grammar of Ornament – the big, big book of the Victorian period – was his research on everything from Pompeiian to ‘Hindoo’ design, right the way through to the Gothic and Byzantine period. He was the one that put a rocket under Victorian interior design and encouraged it to become just as crazy and eclectic as it did.’

Maxi’s Tipi

‘I felt The Dial House tipi shouldn’t be what you’d expect from a tipi. I loved the idea of re-engaging that moment we had in the long summer holidays where we wanted to drag all of the living room furniture out into the middle of the lawn, making it an encampment of chintz. With this design, we didn’t hold back, and used ever single LLB print we had on every surface that could take pattern... it has a childlike charm, is sophisticated but kinky, and feels like we’re being subversive in a rather suburban way. It’s been unbelievably popular.’