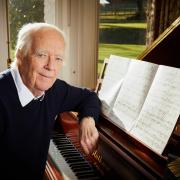

Former Children’s Laureate Michael Morpurgo, author of War Horse, will be guest speaker at a gala dinner hosted by Wiltshire’s Bowood House on April 25. Katie Jarvis spoke to him about his writing, and about how we should commemorate the centenary of the First World War

‘We regret to inform you that your son, Private X, was shot at dawn for cowardice. Yours sincerely...’

The simple letter above inspired War Horse author Michael Morpurgo to tell the little-known story of those who met their brutal end at the hand of their fellow countrymen. He talked to Katie Jarvis about his new novel, and how we should commemorate the First World War

There are no winners in Michael Morpurgo’s books about war.

Not in War Horse, the desperately-moving story of Joey, the young horse whose love for his owner, Albert, survives the atrocities of being caught up in the brutal slaughter of the front line.

Not in Private Peaceful, a book, a film, a play (about to embark on a new tour) and a concert - a requiem, no less, for the British soldiers shot for ‘cowardice and desertion’ by their own side.

Nor, indeed, in any other novel by this national treasure of a children’s author. War: the most complex, divisive, tortuous, torturous subject on earth, explored through deceptively simple prose that explodes with the force of an artillery shell. Moreover, there are no simple good guys and bad guys; all nations, in Michael Morpurgo’s books, occupy a moral no-man’s land.

So you can understand why his metaphorical guns are pointed firmly at our own ‘side’ when politicians come out with jingoistic ideas around the First World War centenary.

“What Gove doesn’t mention and he should - he really should because he’s an intelligent man – he should know that, actually, less than a million of those who died came from this country; that there were two million Germans [who died] who were our enemy who are now our friends.

“The problem with politicians is they’ve always got some axe to grind,” Michael Morpurgo adds, vehemently. “And it’s sad because, of course, it’s not a case of: either we’re proud of our soldiers or we think war is dreadful. They did the most extraordinary thing, those people, with the courage they showed. And of course, you feel respect. But ‘pride’ is the wrong word, somehow. If it makes us feel some sort of sense of national pride – flag-waving – then, no. This was part of a holocaust of a war in which 10 million people died. It must in no way be celebrated; but what you can do is to honour the people who went and didn’t come back; the people who went and came back wounded; and the women who worked and worked and worked to keep the war going.

“It was an amazing time. But it was also a horrific time.”

We all wept at War Horse on the page, and at Steven Spielberg’s remarkable cinematic adaptation. But perhaps even more thought-provoking is Private Peaceful, Michael’s 2003 First World War novel about another ordinary farm-boy, looking back at his life on the eve of a death. Whether it’s the last night of his life or his brother’s, you don’t know until the end. But the terrible truth is, a young soldier’s life is about to be ended by firing squad, found guilty of cowardice in the face of the enemy.

It was a simple letter that inspired Michael Morpurgo to tell the little-known story of these men, who met their brutal end at the hand of their fellow-countrymen: a letter on display at the In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres, written by a British officer, just six lines long: We regret to inform you that your son, Private X, was shot at dawn for cowardice. Yours sincerely.

“The envelope was addressed to somewhere near Manchester, and you could see that it had been ripped open. And what you knew for sure was that there was a moment, in this woman’s life, that would have turned her whole being upside down. This little, short, brief, heartless note.

“The director of the museum – a man called Piet Chielens – told me there were over 300 men shot on the British side and many, many more on the French and the German sides. He said 3,000 [British soldiers] were condemned to death for cowardice in the face of the enemy; also for little things, like falling asleep on duty.”

When Michael got access to their trial reports, he discovered something even more shocking. “How short they were. Around 20 minutes for a man’s life. Some were murderers and you could see why they needed punishing; but the majority of them had already been identified as having nervous problems.”

Although there were specialist hospitals for officers – Sassoon and Owen met at one in Craiglockhart, Scotland – there was little help for those lower down the ranks, who would be sent home to rest after ‘shellshock’, before being returned straight to the unspeakable horrors of the front line.

“Of the 3,000 men condemned to death, only 300 were shot; the rest were commuted to prison sentences. But the 300 who were shot tended to be shot just before there was going to be some big attack, in order to ‘encourage’ the men. So there was method in their – you wouldn’t call it madness; it is how things were then. But when you look at it now, you know it was unspeakably cruel.”

Michael Morpurgo’s own experience of war is stark. Born in 1943, he played in the bombsites that scarred London after the hostilities ended. But it was the physical scars that lingered: he felt the heartbreak his mother experienced, grieving for her brother, Pieter, an RAF pilot shot down aged 21. And he ‘lost’ his own father to the war: while Tony Van Bridge, an actor, was away fighting, his wife - Michael’s mother - met Jack Morpurgo, whom she later married. Van Bridge, quite possibly out of considerateness, distanced himself from the family and emigrated to Canada.

But it was a later encounter that really sparked the War Horse story.

“Funnily enough, in my village in Devon lives the last-surviving widow of a soldier in the First World War - a lady called Dorothy Ellis. It was her late husband, Wilf, who was the person I talked to, 35 years ago, when I first thought of writing a story about a horse going to war.

“He told me what it was like to be a young soldier; what he went through and the story of his pals. He showed me his trenching tool. He showed me photographs – all that sort of thing. I’d read all the poets and the novels, and I’d seen Oh! What a Lovely War and this film and that film. I had some sense of the horror but I had never spoken to anyone who had actually been there. And it had such an impact on me that I sat down and wrote the book.”

And there was another influence, which was also close to home. In 1976, Michael and his wife, Clare, established the charity Farms for City Children, which owns Wick Court at Arlingham. Children from urban areas are invited, with their teachers, to spend a week on one of the charity’s three farms, helping out with all the work and experiencing the countryside at first hand. One particular little visitor stands out: a Birmingham lad, who arrived for his week in 1978, severely withdrawn and with a stutter. He took to farm work as if he’d been doing it all his life. One rainy night, Michael caught sight of this boy, in slippered feet, quietly talking to Hebe, one of the farm mares. He was telling her, without a trace of a stutter, all about his day.

It was both that connection with animals, and that sense of aloneness, that fed into Michael’s writing.

“Story, it seems to me, more than anything I know - and music; the two of them go together - are a way of you feeling not alone. If you’re reading a story and you identify with the people in it, you have a friend as you’re going through.”

Many of his fictional characters spend a lot of time by themselves…

“Exactly. You are the person who is accompanying them through this story. And I’ve learned, just recently, that when you’re not just listening to music but when you’re making music – and it’s really important to do these things – you do it with people; you do it in an orchestra, in a choir; and there’s a terrific sense of belonging and community.

“The arts can bring us together in a way that is – yes, we must say it – spiritual; and it’s emotional as well. And that’s why, for instance, when I go to the play of War Horse or of Private Peaceful, I can feel this silence; this focus. You know that everyone is locked into this story, into this drama. They have suspended themselves completely; they have no ego left. They are simply living this story from what they are seeing and hearing on the stage, and it’s done through music; and it’s done through design; and it’s done through the puppetry; and it’s done through acting. But the great thing is that it’s really meant. And people catch on to that - to its integrity, I suppose - and become part of it and lend themselves to it. It’s an experience which is life-enhancing rather than just a bit of fun.”

As a former teacher, it’s something he wishes educational decision-makers would fully understand, instead of veering towards ‘productivity in education’: “The measurable outcomes which politicians can point to and say, ‘Well, I did this!’”

Which leaves us where we began. With politicians, remembrance, misplaced jingoism, and the vexatious question of how we should mark this First World War centenary.

“My feeling about the whole thing,” says Michael Morpurgo, “is this: we put down poppies, which are red, because that is where the poppies grew, in Flanders Field; but also because of the blood that was shed. But if any war should make us more determined to be peaceful, it is that war. And so we should wear, alongside our red poppy, a white poppy – not because we want to rub someone’s nose in anything but because we ought to be as sincere about our wish for peace as we are about our memory of those who didn’t come home.

“It is what they died for,” he says, with the sheer force of simple truth that defines his books. “They did not die for us to go on fighting wars.”

***************

Tickets to attend the black-tie dinner on April 25 are priced at £150 per person, with proceeds donated to Farms For City Children (www.farmsforcitychildren.co.uk). Bowood House & Gardens reopen for the season on Tuesday, April 1; the start of Bowood’s highly-acclaimed Rhododendron Walks’ annual six-week run will begin on the day after the gala dinner. For dinner tickets, call the estate office on 01249 812102, e-mail reception@bowood.org or visit: www.bowood.org/eventsThis interview by Katie Jarvis is from the April 2014 issue of Cotswold Life.

For more from Katie, follow her on Twitter: @katiejarvis