A hundred years ago the women of Britain were determined to do their bit on the Home Front, but the discovery of some letters in a local family history centre has revealed that one Dorset woman found a very unusual way of reaching out to the sick and injured

At the outbreak of the First World War, Christina Squire was 19 and living with her parents, at Glendale. As she waved her three brothers off to war, she must have wondered what her own role should be. Chrissie, as she was known, kept busy with war time activities such as bandage rolling, and knitting warm garments for the soldiers. But she was not content just to do the minimum, Chrissie found a way of making a unique contribution to the war effort through joining the National Egg Collection.

This was an initiative set up in the early days of the war under the patronage of Queen Alexandra to collect eggs and distribute them amongst wounded soldiers in France to provide additional and much needed sustenance. The scheme continued throughout the war and an astonishing number of eggs (well in excess of 20 million) found their way into hospitals over the course of the four years. Some 64,000 passed through the collection centre in Bridport Town Hall and of these Chrissie certainly contributed hundreds and many of these she personalised, putting her name and address on to them, painting intricate little pictures and sometimes adding a poem or an encouraging word. In return for her decorated eggs she received letters from soldiers thanking her, and giving her snippets of information about their lives. These letters are now held at the Local History Centre in Bridport.

From the letters we learn that Chrissie painted a variety of different pictures on her eggs - sprigs of heather, flowers, black cats with long tails, the Union Jack and the French flag. We know some of the poems she wrote and can deduce that she became very skilful at fitting quite a number of words onto each eggshell. Here is one example received by a wounded soldier in July 1918.

‘Tis but a simple egg I send

But kindest thoughts attend it

And may God bless with happiness

The friend to whom I send it’

Often there was a draw to determine which man in a hospital ward would receive the decorated egg. We also know that some of the soldiers kept the whole egg by blowing the contents out and preserving the shell. We don’t know if any of these eggs are still in existence, but it would be lovely to discover one!

What do the letters tell us of the soldiers themselves? They are written by men of varying ranks and of several different nationalities including British, Australian and Canadian. Together, they paint a fascinating and often heartbreaking picture of life as a soldier in France. We learn of terrible injuries and illnesses borne with extraordinary courage and dignity. We read about the unrelenting hardship of life in the trenches, the comradeship of fellow soldiers and the kindness of nurses. It’s hard to pick out just a few quotations from the letters, but the following are some of the ones which are most memorable.

A Gunner from the Canadian Artillery writes in January 1916: ‘I have a poisoned compound fracture just below R. knee joint. Am doing vey well now. And they expect to save my leg. I hope they do too. Was hit in 5 other places but nothing serious’.

A soldier from the same hospital in France writes: ‘I have been out here 11 months. I have seen life and death, brave sturdy lads in the fullness of manhood marching to take their allotted places in the firing line. I have seen them come back. No picture ever painted, no dreams could make you realise the sight that meets your eyes no thunder claps was ever known when you are between the fire of hundreds of big guns. The scene is one of utter desolation it gives you an idea of what would be the end of the world’.

Many letters give a strong sense of the loneliness of the soldiers, and they express their gratitude to Chrissie that someone has taken the trouble to think of them: ‘I must say it makes every brave Tommy proud of himself when even the young Ladies at home are sending their names and addresses on Eggs to them’. Chrissie was often asked to write back with a photograph or if they can visit her next time they get back to ‘Blighty’.

Corporal Heatley writes on August 14th 1916: ‘I simply admired the verses on the eggs and more so admire the sender so please answer my letter, and I will not forget you in the future’. He signs the letter ‘Your soldier boy’. Private David Davis writes from the hospital in Boulogne in November 1916: ‘I will certainly come to see you when I get back if you don’t mind. I haven’t a young lady yet, but I should certainly like one. I am a rather nice looking young fellow of 22’. .

In the collection, held at Local History Centre, there are two letters from a Canadian soldier, Private H C Hayes, and two from Private John William Baxter who joined a Lincolnshire regiment and then a Scottish one. So it seems likely that Chrissie may have written to these two in response to their first letters, and therefore it may be reasonable to assume that she sent a reply to some of the others as well.

Chrissie never married, whether this was because she lost a loved one during the war, we can only speculate. Her youngest brother Eleazar was killed in action in 1917 and is remembered on the Chideock War Memorial.

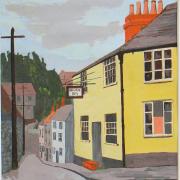

Later in her life Chrissie became landlady of the Glendale Guest House (now Hollow Cottage) on North Road. She took an active role in village life and was known locally as Auntie Chrissie. She died in 1976.

During this centenary year the story of a Dorset woman who provided support and friendship for wounded soldiers in France with her Chideock eggs is certainly one worth telling.