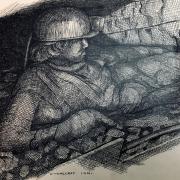

Explorers George Mallory and Sandy Irvine, from Cheshire, tried to conquer Everest in June 1924 and died in the attempt

Most people know that the Earth’s loftiest peak, Everest, was conquered in 1953 by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay. Far fewer know of the brave attempt to defeat the mountain nearly 30 years before by George Mallory and Andrew ‘Sandy’ Irvine in June 1924. They were last seen about 800 vertical feet from the summit and tragically were never to be seen alive again. These two brave souls were both men of Cheshire.

Mallory was born at Mobberley (18th June 1886), the son of a clergyman and one of four siblings, one of whom, Trafford Leigh-Mallory would unfortunately become the most senior RAF officer killed in WW2. Mallory showed his propensity for climbing from an early age, as it is known that he once scaled the church roof when he was but a child. Home for Mallory would have been the hall in Mobberley, at least until it was sold by his father in 1900, around the same time that Mallory departed on a scholarship to Winchester College. It was here that his love of climbing would really be engendered, thanks to one of the masters who took a small party climbing in the Alps each year.

Uncannily Mallory’s climbing partner, Sandy Irvine, was also a Cheshireman, born in Birkenhead (8th April 1902), one of six siblings, with a mother hailing from a longstanding Cheshire family and a father who had Scottish and Welsh roots. Irvine, educated at Birkenhead School, developed a keen interest in engineering, enabling him to fix or improve anything mechanical, and was also a strapping sportsman, an Oxford rowing ‘blue’ no less. These were attributes that brought him to the attention of the 1920s Everest expeditions.

There were three attempts on the mountain in the 1920s (1921, 1922 and the ill-fated 1924 expedition). Whereas the experienced Mallory was ever-present on these adventures, the younger Irvine was new on the final trip, making this his one and only attempt to climb the mountain.

Mallory and Irvine departed these shores for the last time in February 1924, setting sail from Liverpool for the Himalayas, along with two others. The climbing party, once assembled, comprised ten men, including a translator.

Two attempts had already been made to reach the summit before Mallory decided (surprisingly) that the inexperienced Irvine would accompany him on the final attempt that the weather and season would allow. Irvine had proved himself a dab-hand with the team’s oxygen apparatus, however, and maybe this was what Mallory had in mind.

What happened on that final attempt remains a mystery to this day. Starting their ascent on 6th June, by the end of the following day, they had established a camp at 26,800ft, from which they could attempt the final push. The last sighting of them was at 12:50pm on the 8th ‘going strongly for the top’. They never came back.

In May 1999 George Mallory’s frozen body was found just below the height of the duo’s final camp, the remains of a rope still around his waist, suggesting that the two climbers had been roped together at the end. Tantalisingly it remains a mystery whether the brave climbers had reached the summit and perished on their perilous descent, or whether calamity overtook them on the way up. Mallory remains buried on the mountain that had become his life’s obsession. He was not quite 38 when he died. Irvine’s body has never been found. He was just 22.

The word hero is used far too often and too casually nowadays, but these men were genuine heroes for casting safety asunder and trying to be the first. Mallory, as with many of the 1920s climbers, had seen action in the Great War (he was at the Somme). Irvine was of a younger generation, lionhearted and determined to push himself to the fullest extent of his endurance.

The best commemoration to the two men is perhaps the one in a window in the Chester Cathedral cloister as it remembers ‘two valiant men of Cheshire … who adventured their lives even unto death’. The two of them were inseparable at the end, after all, and should be remembered together.

The last word should perhaps be left to Mallory, who coined an immortal phrase in America on a 1923 lecture tour, when asked for the umpteenth time why he wanted to climb the mountain. “Because it’s there.” Such is the draw for the mountaineers who risk everything in their pursuit of the highest peak.

References

Into the Silence – the Great War, Mallory and the Conquest of Everest (Wade Davis, 2011)