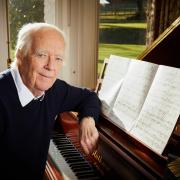

Artist, owner of the beautiful Lypiatt Park and the Woolpack Inn in Slad - the multifaceted Daniel Chadwick has exciting plans for the future, including a sculpture park dedicated to the work of his father, the sculptor Lynn Chadwick...

IN THE now-legendary beard-growing competition at the Woolpack in Slad, the pub's owner, Daniel Chadwick, came a commendable third. Being rather taken with his elegant whiskers (Edwardian with a modern twist), I feel this could have been a diplomatic decision to avoid cries of 'Fix!' If Daniel Chadwick feels the same, he's far too courteous to voice the opinion.

Instead, one of the pub's many other hirsute (for the occasion) characters carried away the prize of 30 pints of beer. And, trust me, there's no shortage of characters, both past and present. It was here that Laurie Lee held sway until the end of his days, regaling fellow drinkers with vignettes of his eloquent life. Ben Wordsworth was another regular, now sadly missed. It was he who introduced the seminal Thursday Lunch Insults (popular, presumably, with the sort of masochists for whom self-doubt is never enough). Nowadays, it's the actor Keith Allen who regularly serves behind the bar. (When someone first told me, I thought they were being wittily ironic. They weren't; he really does.)

And, of course, another of those characters is Daniel himself. The man who bought the pub 10 years ago because he couldn't bear to see it languishing, ownerless, when so many people loved it. It's strange to see him there, sitting in the sun with a pint of Uley bitter: one of the crowd. It's a bit like that famous Rubin vase optical illusion. View him in this context, and his tailored trousers, immaculate shirt and white braces assume a 'Stroudie' look of farmers' markets and eccentric second-hand bookshops.

But place him in a different context and those same clothes appropriate a sartorial elegance, more in keeping with his alter ego. For Daniel Chadwick, owner of the idiosyncratic Woolpack, is also the owner of Lypiatt Park, one of the most beautiful and historic private estates in the region.

****************

WHERE I have a (very nice) wrought-iron umbrella stand in my hallway, Daniel Chadwick has a bronze by one of the best-known British sculptors of the 20th century. Where a Constable print adorns my wall, he has a Damien Hirst. ("He gave me that to say thank you very much for finding him Toddington. He didn't need to give me anything.")

And, to cap it all, Lily Allen has never asked to record an album in my sitting room.

Mind you, we are talking about a sculpture by Daniel's father (the late Lynn Chadwick

Artist, owner of the beautiful Lypiatt Park and the Woolpack Inn in Slad - the multifaceted Daniel Chadwick has exciting plans for the future, including a sculpture park dedicated to the work of his father, the sculptor Lynn Chadwick

); a painting by his best friend (Damien Hirst); and an album by his other-best-friend's daughter (the lovely Lily). And apart from anything else, having connections like these does provide some outstandingly entertaining anecdotes.

"We had Lily recording her new album in here for a month just before Christmas. We rented out this whole wing," he explains. "Her only question before she arrived was: 'Is it warm?' I said, 'Yeah, yeah, of course it is'. I put the heating on for a week and there was still ice on the inside of the windows! So I had to take up the floor myself and put in under-floor heating in three days! I'm glad I did, though; it's been marvellous."

Daniel Chadwick is showing me round the glorious house at Lypiatt Park. It's a fairytale-looking building, with turrets and castellations and splendid Gothic windows. It even has fairytale associations. One of its earliest owners was Dick Whittington, said to have won it in a bet. More deliciously sinisterly, Robert Catesby, leader of the gunpowder plot, is reputed to have met here with his co-conspirators - Tresham, Winter and Guy Fawkes - to finalise their dastardly (but ill-fated) plans to blow up the Houses of Parliament.

The day I'm visiting signifies another landmark in its long, long history. For it's today that it fully belongs - lock, stock and barrel - to Daniel. "I think it's today - or it could be tomorrow," he muses, sitting in the modest room where much of the day-to-day living gets done. On the '70s record player, The Doors are singing cryptically. The space should be dominated by the amazing art works that hang there - yet one-year-old Eva's playpen is just as much of a statement.

Actually, that's the interesting thing. This could be a daunting house - it's beautiful, huge and rambling - but it has an intimate family feel to it. As I arrive, a young woman is gardening outside. "Hello, I'm Juliet, Daniel's wife," she says warmly. (She's a talented artist - an illustrator - herself.)

The two of them have filled the estate houses with friends. There's yellow and red maypole ribbon draped around one of the trees from a recent party. The magnificent wooden doors stand open in the bright sunlight, and there are various characters to bump into round the grounds: Amaury Blow; Keith Allen, tinkering with a boat he keeps in the courtyard.

"When my father first bought Lypiatt Park, the house was more or less derelict," Daniel says. "No one would touch it with a barge pole. After the war, they were demolishing houses like this, and this one was about to go, too. He spent every penny he ever made on this house."

As the new owner, does that not have a slightly sinister resonance?

"Yes, but it's a nice thing to spend it on."

It had always been Lynn Chadwick's dream that one of his children would take the estate on - he spent nearly half a century restoring the house and its 10 acres of garden - but that hope had seemed an increasingly unlikely proposition. "It's been an incredible journey because I've had to buy out my family, which for a while seemed unachievable. But the moment he died - in this room, the same room where little Evie was born - I thought, 'Oh my God, we cannot let this go!' I honestly hadn't known I would feel like that," Daniel says.

That's not the only Lynn Chadwick dream that's on the brink of being fulfilled. For alongside the house, Lynn also bought a large tract of land in the Toadsmoor Valley. Here he began to create a permanent exhibition of his work. The catch was that this fiercely private artist did not relish the idea of opening the estate to outsiders. His son, however, feels differently. In fact, by this time next year, the Lynn Chadwick Sculpture Park should be up and running. It's a large-scale venture, undertaken in conjunction with Rungwe Kingdom of Pangolin (one of Britain's leading sculpture foundries, with its base in Chalford), designed to attract around 60,000 visitors a year. Importantly, it will be the UK's only permanent showcase of its kind dedicated to one artist.

"Lynn was very prolific and we have a copy of every sculpture he's ever made. Inevitably, I had a lot of reservations about the project, to begin with. Lypiatt Park is a sneakily private place, but, at the end of the day, we thought: It's bigger than that! We live here and that's fantastic; and I have a lot of respect and love for my father.

"Lynn didn't want it when he was alive, of course - he couldn't bear the public! He started putting sculptures in the valley, and we talked about it a lot, but it all seemed too complicated and undoable. He would be so happy to see what's going on."

What Lynn would particularly like, to be sure, is the fact that Daniel himself has designed the carbon-zero visitors' centre. Like his father before him, he has spent time working for an architect - in Daniel's case, it was the deconstructivist architect Zaha Hadid.

"To begin with, I designed a building that was bird-like: two big pyramid shapes. But then I thought, I don't want to shove that on everybody who lives in Eastcombe, so I made a much more modest building.

"Besides which, we don't really want to make a powerful statement with the architecture. It should be a blank canvas on which to show the sculptures in the most practical but beautiful way possible. It's a bit like an aircraft hangar - simple curves but entirely glass - so you arrive and look through the glass and beyond to the sculpture park."

Standing atop the raised terrace in front of the house, you can see over the 30 acres where the sculpture park will be. The setting is stunning - a mini plateau surrounding by the rolling Gloucestershire hills; and there, as if grazing animals or people out for a walk, are some of Lynn's monumental sculptures. Such as two sitting figures, leaning conversationally to one side, viewing something in the middle distance, their geometrical shape both abstract and hard-lined, yet wistful and eminently human at the same time. There's a bird-like figure with wings and tail feathers that further blurs the line between man and beast.

In the house itself, which won't be open to the public, there are more besides - as well as pieces by Daniel himself. Although very different - where Lynn's work is harsh, Daniel's is more sensual and rounded - the synergy between father and son is obvious on one plane in particular: the fascination with space and design.

Lynn was, by all accounts, a Rodin-esque figure, larger than life, who created his own private fiefdom at Lypiatt. Daniel is equally engaging: intelligent in his analyses, open, and with a chuckle that surfaces unexpectedly, often, and infectiously.

Was art a natural choice for Dan?

"My father wasn't encouraging, but that was for good reason. When he made it, there were only three or four artists in this country making a living from it. It wasn't something he would recommend to any of us, for that reason.

"But in fact, the big advantage of having a father who was an artist and making a living from his art was I could see it was possible and it is possible. And I think a lot of my contemporaries coming here were inspired to see that this house was totally funded by sculpture. My friend Marc Quinn (the British artist particularly known for Self, a sculpture of his head made with his own frozen blood) definitely saw that and went on to push himself; and to a lesser degree Damien (Hirst), though he was already so incredibly focused."

As an artist, Daniel's own work is extraordinary and varied. On the wall of his dining room, there's a huge plain white, shimmering contoured surface - 'Near Paradise' - that just cries out to be touched. In fact, when you do run your hands along its planes, they reveal even more than your eye. The curves and bumps transform into what they are: a map.

"It's Painswick - the Holcombe Valley. I use data I buy from Ordnance Survey. It's all about the recurring themes in nature: it could be a frozen moment or a ripple of water. It leaps into life, if you start to touch it." He moves away to get a longer perspective. "It picks out things you don't normally see. Actually, these dots here are absolutely typical of burial mounds. I don't think anyone knows they're there."

Other works are full of movement - like the blue balls that are twirled by hidden motors; some are humorous, such as the small foam Smurf-like shape that formed as a by-product of a different project.

"Does it have a name?"

"Teenage existential angst," Daniel chuckles.

He's made himself a successful and lucrative career with his art, particularly concentrating on commercial commissions. The down side of that is that many of his pieces are hidden away in office spaces and not on view to the public. He's currently working on one that will be seen, in Snow Hill, Birmingham - set to be the biggest sculpture in the city: an incredible flocked red and Perspex shape more than 10 metres tall, inspired by the natural form of twigs - a figurative, organic piece, entitled 'Somewhere in the universe'.

Perhaps his name will leap to further public prominence with his next big project, which combines almost all of his passions: art, design, engineering and sustainability. For alongside his art, he's working on a design for an electric taxi, which he's hoping will be adopted in the near future by a major world city. "I hate all cars at the moment because they're heavy - big metal engines and a big heavy metal frame - and essentially dinosaurs in design terms. So I've gone back to first principles and designed my own. The first thing was to cut down the number of parts by making it symmetrical so every corner is identical; it looks great, too.

"I love all the technology we come up with - I love the way we use our silly big brains."

It's a wide-ranging portfolio, but all he touches has one thing in common: "Optimism," he says.

We sit looking at photographs on his computer: his work; Lynn's work; the beard-growing competition at the Woolpack. It's a multifaceted life, dominated by art, defined by friends and good humour.

"The art world has changed a lot recently. We've had a period where the more intellectual art has been the only one that's was acceptable; and I think they've been jolly nasty to the other artists who try to make nice-looking things. I was very, very unfashionable to begin - for example, the fact that I had any kind of interest in design was frowned upon - but now what I do is coming back into fashion," he says.

"Well..." he adds, with that wry chuckle, "nearly."