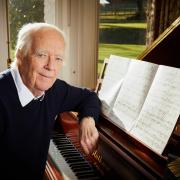

It takes a particular talent to photograph horses well. Bob Langrish has that talent, as his 4000,000 picture library shot all over the world clearly shows. Katie Jarvis met up with him

THE BRUMBY in the photograph looks so docile, you could almost stretch out your hand and pat its chestnut muzzle. Salt-and-pepper mane ruffled by the wind, it raises its head momentarily from grazing on the stubby Australian grass: wild, sturdy and free.

You'd think, from the ease of its expression, that anyone could pick up a camera and snap such a shot. Actually, that very feeling is a testament to the skill and knowledge of the photographer, Bob Langrish.

Not heard of him? Surprisingly, not many people have outside the equestrian world. But when it comes to taking photographs of horses, he's nothing short of a legend. In fact, the filing cabinets that dominate his office in Bisley hold more than 400,000 pictures covering everything from noble Acehs in Indonesia to cute snaps with the 'Aah' factor: it's the most comprehensive library of its kind in the world.

It's thanks to the experience he's gained during more than 30 years of photographing these animals that he's able to capture moments such as the contemplative Brumby. "It's so difficult to take pictures of these Australian wild horses: you can't get close," Bob says. "They get shot at out of the sky by the government who track them in helicopters. They're culled because they're considered such a pest."

They're certainly fey creatures, which have lived in the wild for more than 150 years. No one quite knows where their name comes from: some speculate it's courtesy of a Sergeant James Brumby who abandoned his horses when he left New South Wales for Tasmania at the beginning of the 19th century. Others say their ancestors were escapees of the 1851 gold rush.

"I'm working on a book of wild horses at the moment - there are very few left in the world," Bob says. "Apart from the Brumbies of Australia, there are only really the Mustangs of America. The challenge is trying to get anywhere near. When I was working in Canada, I was charged by a stallion who thought I was after his mares. I knew I couldn't run as fast as him so I stood my ground - luckily, it worked!"

The Princess Royal herself has most unusually agreed to write a forward to that book - Wild Horses of the World - which will be published by Hamlyn later this year.

But it's far from just wild horses that Bob photographs. Of the estimated 250-plus pure breeds you can find around the world, he's taken pictures of more than 230 of them. That's involved scrambling his way around Russia's Caucasus mountains to find the lightning fast Karabakhs; being held up at machinegun-point in Turkey where guards mistakenly thought he was trying to infiltrate a nuclear submarine site; and talking his way into Indonesia where the media are usually shown the door.

Mind you, Bob's not your typical 'media' man, as many who've seen him at work will testify. Once, when he was out with the Beaufort, (long before the current ban), he found himself in the company of the Prince of Wales. "At the time, I was doing all the hunting photography for Horse and Hound, and I'd run and walk 15 miles in a day to get the pictures.

"I rounded a corner and there was Prince Charles out on point, looking for the fox. I said 'It's OK, Sir; I'm not paparazzi'. He said, 'I gathered that because I've yet never seen a Fleet Street photographer follow the hounds in running shoes!'"

You'd probably imagine Bob Langrish grew up surrounded by these animals who've formed such a part of his working life: well, you can forget that idea. The son of a police chief inspector, he spent his childhood in the urban confines of South London. While he rarely saw a horse, he knew he wanted to be a photographer from an early age: The family timeshared their bathroom with a darkroom.

After school, Bob eschewed the offer of a 'gopher' job in Fleet Street for a secure post with the police, but continued to 'moonlight' at the weekend, covering motor-sport events. When he was forced to choose between the two, it was a no-brainer. He could earn more taking photographs at the weekend than during his regular Monday-to-Friday beat.

But when he moved his young family to Gloucestershire to concentrate on taking motor-sport pictures for specialist magazines, disaster struck. Almost before the ink was dry on the mortgage form, the company he was with went into receivership.

"So my wife suggested I try switching to horses. I didn't know anything about them, but the best way of learning is by your mistakes. So I began to go round all the local Pony Club events - Beaufort, Berkeley, Ledbury - and the horse shows, selling pictures to riders.

"Parents are always going to buy pictures of their children on horseback. You just need to be able to take a photograph which is good and which shows that child or rider jumping a fence well. The most important thing is split-second timing; even using eight to 10 frames a second, you can still miss the crucial split-second of 'bascule' - when the horse's neck and back bend over a fence. That's when it looks at its most powerful.

"A good photograph is a combination of composition, timing, and knowing the fences a horse will look better over. If you've got a straight, upright fence, very narrow, the horse doesn't have time to bend. But if you have a hedge or parallel rails, they work well."

Through his contacts, Bob began working for magazines, as well as compiling books about horses. One of the first he did was with leading rider and trainer, Jenny Loriston-Clarke.

He's also covered many big sporting events. "One of my favourite moments was in Germany when the British team won the World Showjumping Championships with David Broome, Derek Ricketts, Malcolm Pyrah and the late Caroline Bradley. We all got together afterwards and did a World Championship poster. I was made to feel part of the team."

But his big break came when children's publishers Dorling Kindersley asked him to compile the Ultimate Horse Book, which involved him travelling the world seeking out different horse breeds. The journey didn't stop there. Since then, working on many different equestrian projects, he's travelled an amazing 1.4 million miles, which has taken him to almost every region on earth.

He's even just returned from Iran, where he was one of the few Europeans ever to be invited to the Aspahan Horse Festival, held in the country's second city, Isfahan. "I was treated incredibly well there. After the festival, I took a couple of internal flights to see some of the horse farms near the Caspian Sea. It was a completely different world - far more rustic. One day, I visited a village where somebody had their champion stallion tethered to the ground just outside a mud hut."

If there's a country he still longs to visit, it's Mongolia; but he's already found his favourite breeds: Arabs and Andalucians for their expressive movement and power.

He also knows where horses have it best. "Here in the UK, without a doubt," he says. "They're looked after so well."

And there's another certainty, too: that Bob himself will choose lens over saddle any day. "People who learn to ride in later life look like a sack of potatoes," he says. "I'd look like two sacks.

"When it comes to riding - no thanks! I'll stick with my camera."

For more information on Bob's work, visit www.boblangrish.com or ring him on 01452 770140.