Recounting an infamous night, 100 years ago, when the horrors of the First World War reached the doorsteps of the people of Derbyshire and Staffordshire

MARY Morris died with a Bible still in her hand, her sermon in the Christ Church Mission Room on Uxbridge Street in Burton brought to an abrupt end by a shower of bombs that fell from the night sky.

Mary shouldn’t have been there at all but safely at home in Brighton. Having been persuaded to stay on to give one last sermon, she was in the act of delivering this when the bombs fell and may only at the last second have understood what was happening to her. The shrill whistle of high explosives heralded her demise and she perished with five of her congregation with a further 72 injured.

Mary’s story is just one tragedy from an infamous night, 100 years ago, when the horrors of the First World War reached the doorsteps of the people of Derbyshire and Staffordshire.

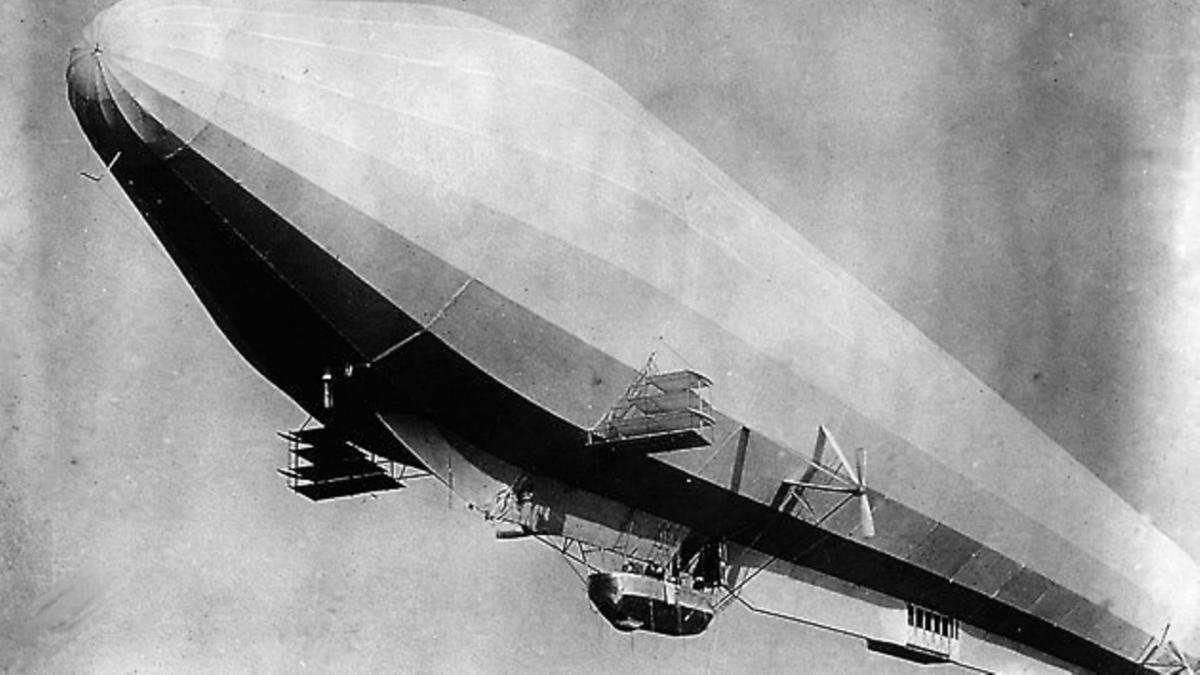

31st January 1916, was a night of terror, as German Zeppelins mounted a moonlight raid that left a trail of death and destruction in its wake. The story has been pieced together by Sir Henry Every, whose Egginton home was close to the flightpath on that fateful night.

A century later, Sir Henry believes there are few people who know the full truth of this shocking attack on civilians, which brought the war into the living rooms and workplaces of the people of Burton, Derby and beyond. Until then, these towns were too far inland to be considered at peril and not of sufficient strategic importance.

Neither town had a full blackout in place – indeed there were no regulations enforcing the turning off of lights. It was this failure that would lead to so much death and misery.

Sir Henry says: ‘It seems the Germans didn’t believe they could readily win the war in the trenches, by sending our merchant ships to the bottom of the ocean, or even by bombing London. But they thought they could show the British people what war was really like through Zeppelin raids, bringing the war to the home front and prompting people to rise up against the politicians and sue for peace.

‘I had long known about the raid on Burton and wondered why a small Midlands town should be singled out when many larger places had escaped. Surely not because of the Burton breweries!’ says Sir Henry. ‘Last year when a First World War exhibition was put together in the village, a reference to Zeppelins coming over Egginton was found in the primary school records. Following up on this I found that the Burton raid also involved Derby and several towns in the Black Country, making this one of the most destructive Zeppelin raids in the war.’

The Egginton School log book entry for 1st February 1916 states:

‘Last night, January 31, between 8pm and 9pm, German Zeppelins passed over Egginton, quite near to the school. The head teacher extinguished the light in the playground belonging to the Institute and called upon the men there to put out the inner light. Two infants are absent today through the air raid and many others are tired, having lost their night’s sleep.’

Egginton had a narrow escape but those living to the north and south were not so fortunate.

The Zeppelin raids on Derby and Burton were almost certainly a mistake, with Liverpool the intended target. ‘Navigational errors are hard to understand today but, back then, air travel was still in its infancy and navigation was far from a precise science, with night flying rarely undertaken.’ Neither town was expecting, nor was prepared for, raids, with street lights on and trams running, presenting an inviting target for a payload of high explosives and incendiaries. Derby, having received warnings managed to dim the lights and missed a first wave of potential attacks. Poor communications meant that Burton wasn’t able to heed the same warnings and therefore suffered badly. But Derby hadn’t truly escaped either and was caught at the tail end of the raid, having made the mistake of thinking it was all over.

Sir Henry says: ‘It’s easy to imagine the horror. In 1916 aircraft were still a novelty. Many people would only have heard about aircraft, probably rarely if ever seen them and these Zeppelins appeared to be huge, even from 7,500 feet. Once they started attacking the towns it became a night of real terror.’

It is believed that nine airships raided England on the night of 31st January/1st February 1916. This is how the story unfolded:

Noon: The airships leave Germany and head for The Wash, looking to find their way to Liverpool.

6.45pm: Airship L21 is spotted above Derby but, with lights out, it moves on.

7.45pm: Airship L13 passes over Derby.

8.20pm: L20 bombs Stanton Ironworks, the terror begins.

8.35pm: L20 reaches Derby but drops no bomb.

8.30-9.45pm: Three Zeppelins, L15, L19 and L20, reach Burton, the brightly-illuminated town being an easy target. It was reported that 20 electric street lamps, more than 200 gas lamps, and lights along the railway track, combined with brightly-lit shops, made the town clearly visible from the air.

L15 was commanded by Kapitan Breihaupt. His report of the raid shows just how off course he was: ‘At 8.30pm, the ship was over the west coast; a large city complex divided in two parts by a broad sheet of water, running north and south and joined by a lighted bridge, was recognised as Liverpool and Birkenhead. After dropping parachute flares, the lights throughout the city mostly went out. From 2,500 metres, 1,400kg of explosive and 300kg of incendiaries were dropped in four crossings of the city, mostly along the waterfront.’

Meanwhile, L20 and L19 believed they were attacking the Sheffield steelworks. Instead, they were raining death on The Christ Church Mission Room in Burton where Mary Morris and her 200-strong congregation suffered the worst of the carnage. Houses in Shobnall Street were also targeted, with a total of 15 people killed in Burton.

10.05pm: Having missed its original target, and venturing further west than any other airship, L14 turns back somewhere near Shrewsbury.

Midnight: L14 drops bombs on Overseal and Swadlincote, causing minimal damage.

12.15am: L14 is attracted by the lights of Derby which were starting to come back on after it was believed the airships had all retreated. The targets were well chosen and included Rolls-Royce, the loco works and gas works. Only one bomb landed within the Rolls-Royce site, meaning damage was limited, but five landed at the loco works and three devices were dropped on the gas company’s Litchurch premises, but mercifully failed to explode.

Midland Railway’s site took the brunt in Derby with three being killed instantly and one more dying later from his injuries. The toll from the night was recorded in the Derby press as 61 dead and 101 injured.

However, more recent historical accounts make the picture even bleaker, with the raid on the Midlands on the night of 31st January /1st February 1916, noted as one of the heaviest of the First World War. In all, it is believed that 70 people were killed and 113 injured with widespread damage and destruction from over 200 high explosives and more than 170 incendiaries.

But the story does not end there. Despite suffering engine failures, all but one of the airships reached home safely. L19 ditched in the North Sea with failed engines and malfunctioning radio equipment during the night of 1st–2nd February. The airship with 16 crew members clinging to the floating wreck was discovered by a British fishing trawler, the King Stephen. When asked for rescue, the trawler’s Captain William Martin refused. In a later newspaper interview he stated that the nine crew of the King Stephen were unarmed and badly outnumbered, and would have had little chance of resisting the German airmen if after being rescued they had hijacked his vessel. An alternative explanation, suggested in a 2005 BBC documentary, is that the King Stephen was in a zone in which fishing was prohibited and Martin feared that returning to port with a large number of German prisoners would attract the attention of the authorities to this. Martin sailed the King Stephen away and reported his encounter with L19 on return to his home-port of Grimsby.

In desperation, the L19’s crew threw a bottle with messages into the sea as a last hope of rescue. When Royal Navy ships made a search of the area, no trace was found of the Zeppelin or her crew. Six months later Swedish fishermen found the bottle containing the last messages from the airmen and a final report on their mission. These surviving relics were displayed in an exhibition at the National Maritime Museum in London in 2001.

ROYAL CROWN DERBY ZEPPELIN MARK

On the night of the raid in Derby, the King Street Royal Crown Derby factory was firing a kiln. When the air-raid siren was sounded the kiln fires had to be dowsed and it was not known if the contents would be spoiled or not. When the kiln was opened, the contents were found to have fired well. In memory of the event the whole kiln load was marked with an airship and moon mark.

In the centenary year of the raid, Royal Crown Derby is launching an appeal to see how many of these pieces it can find and record. An average kiln load at this time would hold approximately 100 items. These pieces are therefore very rare.

They are also important, as the story of the Zeppelin mark demonstrates the resilience and hope of Derby people in the face of adversity.

Royal Crown Derby is currently displaying six pieces; two from its own museum and four on temporary loan from private collectors.

If anyone has any Zeppelin-marked items in their own collection or has spotted one in a museum, then please get in touch with Royal Crown Derby’s museum curator Jacqueline Smith, email: jsmith@royalcrownderby.co.uk or call 01332 712886.